Latest news about Bitcoin and all cryptocurrencies. Your daily crypto news habit.

Many act like post-scarcity is some pipe-dream. The stuff of utopian fairy-tales and science fiction. I beg to differ. Actually, I think in many respects, it is already here in the US. We just don’t see the abundance right beneath our noses because our current economic paradigm makes it incomprehensible.

Post-scarcity is an economic situation in which the production of a good outpaces its demand.

But when I take a step back, I see millions of pounds of excess clothing being dumped in other nations. I see free couches on the side of the road. I see ballpoint pens that people take from banks without blinking an eye. I see so many entertainment options, that there are whole channels dedicated just to telling you what’s on other TV channels.

At the same time that income inequality is rising, and people are homeless and going hungry, I see people buying slick FitBits and fancy cars. So what of homelessness? Surely I can’t deny scarcity when people are hungry?

While I do believe that many types of scarcity do exist (and some may always exist), I don’t think that scarcity is to blame for homelessness. I think Capitalism and Socialism are to blame. Because Capitalism is so prevalent in the US today, I’m going to focus on it rather than on Socialism. But my critiques and comments apply to both. First, I’m going to explore the nature of post-scarcity. Then, I’ll turn to why nobody knows what to do with it and what’s needed to change that.

Two types of post-scarcity: Products and financial resources

Discussions of post-scarcity typically center the conversation around products, specifically. I suspect this is because financial resources are valued only for the sake of the products they allow a person to purchase. Still, the distinction between these two types of post-scarcity has important implications for why post-scarcity is incomprehensible from Capitalist (and Socialist) frameworks. These implications will be spelled out further in the next section.

Products

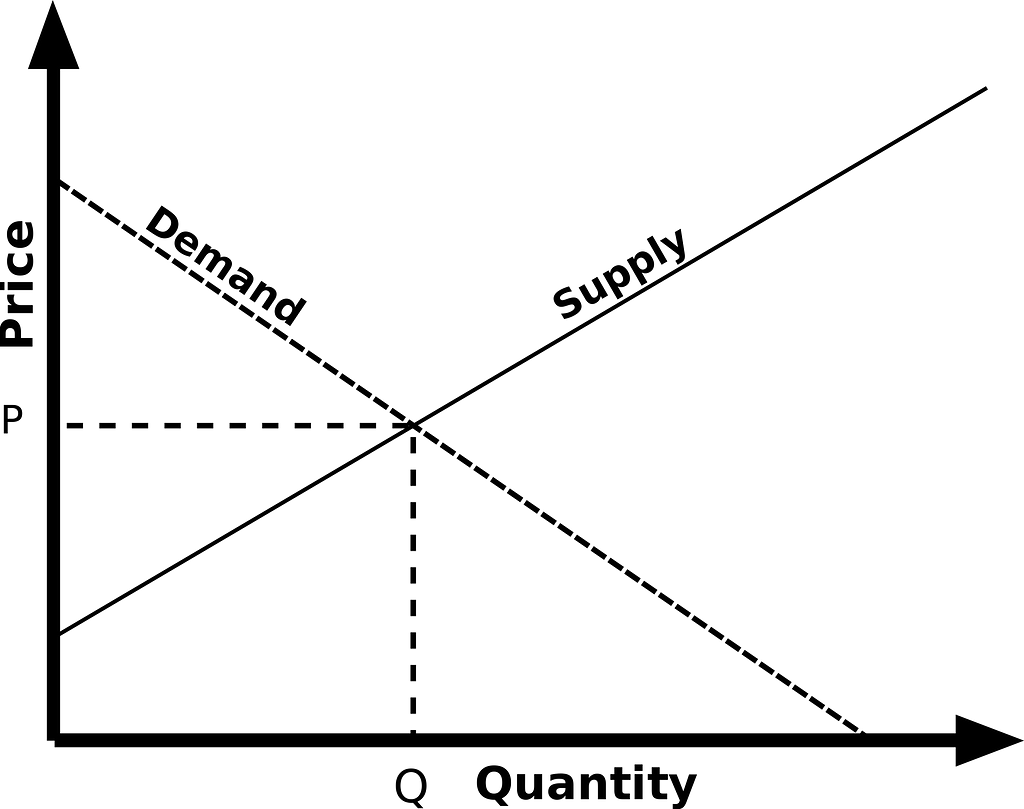

Products are typically imagined as physical goods. The resources and labor for these physical goods are finite, and thus keep the supply-and-demand curves in check (at least from a Capitalist paradigm). Although advances like the industrial revolution or Henry Ford’s assembly line may substantially cut down on the cost of raw material extraction and labor time, the theoretical limits of resource extraction have generally (and prematurely) squelched any notion that supply could continually overwhelm demand. And so technological and societal progression fuel the familiar trickle-down of products — from being rare luxuries to being mundane goods. Meanwhile, the price of these products approach but never reach zero.

Conventional supply-and-demand curve

Conventional supply-and-demand curve

Less commonly, people consider intangible, information when thinking about goods. These goods require little in the way of physical resources (just the hardware and infrastructure that stores and retrieves the goods), and thus have largely reached the post-scarce status.

When I refer to post-scarce goods, I am referring specifically to goods whose supply capacity is greater than their demand. To be clear: not all post-scarce goods are actually distributed to all those demanding, but they could be for nearly $0. This is particularly common for information goods, such as songs or films (for which the cost of obtaining and distributing copies is negligible, but for copyright infringement laws). Some physical goods, however, can also be post-scarce (for example, produce, of which 43 billion pounds is thrown out by supermarkets annually, presumably because local demand is not keeping up with perishability).

Financial resources

Just because someone is born into a world of scarce resources, however, doesn’t necessarily mean that they will personally experience the full effects of that scarcity. While there may be finite products available, some people are buffered from that scarcity via their physical and, for our purposes here, economic ability. That is, the rich and powerful feel the scarcity much less than their poorer and weaker counterparts.

With the advent of civilization (and possibly earlier), humans above the subsistence-level have participated in the practice of wealth-signaling. Once a person has more than enough resources to meet their basic needs, they are able to communicate their relative status to others by deploying money toward unnecessary, flashy things (like jewelry), presumably to attract mates, to win friends, and to influence people.

When I refer to financial post-scarcity, I am referring specifically to a person’s ability to obtain basic physical necessities, and still have money to purchase luxuries (or luxurious versions of instruments for survival, i.e. a New York penthouse, organic produce, or name-brand clothing).

Capitalism and the two types of post-scarcity

While Capitalism fundamentally cannot make sense of post-scarce products, it is no stranger to financial post-scarcity. In fact, that’s the name of the game: if you want to sustain your physical security, you need to become financially post-scarce. Let’s unpack this a little further.

Capitalism was birthed out of a long economic tradition of using physical dollars (fiat) to track value stores. Because most resources were scarce, in order for ledgers of value-exchanges to be accurate, the fiat also needed to be scarce. And this made intuitive sense anyway: I give you a pearl, you give me a physical dollar. We both exchanged something physical and finite, and this seems fair. Thus the scarcity of the good dictated how many fiat units (units of scarcity) were given back in exchange.

This fits tidily with conventional understanding of resource limits. Nobody is arguing that everyone should be given universal luxurious good — say a bar of gold. But, there does seem to be a belief that there is enough to cover everyone’s basic needs (hence, the call for universal basic income-UBI). People are frustrated that some people buy 10 Apple watches, while others are just trying to afford an apple.

UBI is aiming to achieve financial post-scarcity for all (that is, all basics are met, and any extra income can be spent on “luxury” or relative wealth-signaling). But it’s just not possible to recognize post-scarcity inside an economic paradigm which is constituted by scarcity. Capitalism manifests as competitive markets — it’s not so much about what you have as it is what you have compared to others. To make something universal in Capitalism, is to make it value-less. Hence the familiar constraints of inflation.

Zero-sumness, Capitalism, and Post-scarcity

The intrinsic nature of competition over scarce goods, the zero-sumness of Capitalism, is precisely what makes post-scarcity seem incomprehensible. This is the case both for products, as well as for a notion of universal financial post-scarcity (any viable form of UBI). Laissez-faire Capitalism simply wouldn’t compel entities to create post-scarce goods; and natural capitalistic markets would snuff businesses out that do (because the cost would quickly plummet and put the creator out of business).

Regulated Capitalism sweeps this problem under the rug by creating artificial scarcity. This can happen in the form of subsidies to competing products, the creation of jobs that weren’t previously necessary, or — perhaps easiest to illustrate — in the form of IP laws. So enamored with scarcity, are we, that we actually demoralize treating post-scarce goods as post-scarce. If you share a film or academic journal article, you’ve violated the law, and stolen from someone. From a Capitalist paradigm, scarcity is itself what imbues a good with value. To pirate content is to “steal” that scarcity from the IP holder.

To be clear— I am not condoning piracy. Unfortunately, in our Capitalist world, piracy really does result in revenue loss for hard workers. I do, however, want to be blunt that Capitalism puts us in a very absurd dilemma. To spread knowledge and access to information is infringing on IP law: To add value to the world, is a crime. To eliminate scarcity, is unlawful.

Aaron Schwartz was put on trial by Elsevier for unauthorized access of research articles (many of which were publicly funded).

Aaron Schwartz was put on trial by Elsevier for unauthorized access of research articles (many of which were publicly funded).

This is why Neo-Liberals — despite hating government regulation — have a love affair with IP laws. If you want to make money in a system that values scarcity, the only way to make a post-scarce good scarce (that is “valuable”) is to monopolize it and charge a %100000000 markup fee to access it.

So what the heck are people doing with post-scarcity?

People are largely just ignoring post-scarcity of goods. In the face of post-scarcity, we fabricate scarcity and try to morally justify it. With respect to physical goods, we are fine with grocery stores throwing away produce — rather than just lowering the price (I mean, they make the most money this way, and they have to make a living, right?). With respect to information goods, the law is fabricating scarcity with regulations, throwing away a person’s experience of listening, reading, or watching (But, if we make an unauthorized download of that journal article, somebody’s losing out on income that should be their’s, right?). This artificial scarcity is a bizarre band-aid on a bullet-hole in Capitalism.

Meanwhile, we forego buying that extra case of strawberries and streaming a movie rental, and save up to buy that new car — that hot new wealth-signal to show our friends that we’ve got resources to blow.

We simply lack an economic paradigm which can account for the increasing post-scarcity of products. So, we reject their existence — claiming that the labor or the resources that went into a product render it scarce. But post-scarcity is not about what is theoretically limited by physical properties of the universe — it is about our ability to outproduce our actual needs and actual desires. And this is doable for many products (granted not for all, and perhaps not for any of the newest physical products).

What should we do with post-scarcity?

In short, we need an economic paradigm that makes the value comparison of post-scarce and scarce goods comprehensible. In Part 2 of this series, I will argue that what is needed is a hermeneutic valuing system. Such a valuing system understands that the value of a good is not some abstract concept floating around “out there” waiting for the invisible hand to discover. Instead, the value of a good lies not in what price tag the “market” will bear, but is constituted by the intrinsic value a product or service has to a particular person at a particular time. The value I get from watching a film might be greater than the value I get from drinking a cup of coffee — despite the fact that the supply of films is infinite and the supply of coffee is finite. Such an economic paradigm rejects the notion that a post-scarce good is valueless — and makes two ethical assertions: 1. post-scarce goods shouldn’t be squatted on and kept from people who can’t pay some universal arbitrary price tag for it, and 2. creators and distributors of post-scarce goods should be reimbursed for the real value they generate — not left in the supply-and-demand curve dustbowl. I will expand these ideas in greater depth in Part 2 of this series.

What should people do with post-scarcity?

Post-scarcity is here, now. First and foremost, it needs to be recognized and validated. If all we legitimize is scarcity, then scarcity will be all that’s legitimate. The only thing keeping us from unlocking greater abundance is our scarcity-centric economic paradigm — one which equates wealth with how many things you hoard. If we welcome post-scarcity and the new paradigm it demands, we can change the definition of wealth from how many scarce goods you hoard, to how much abundance you create.

I am building out the egalitarian infrastructure of the decentralized web with ERA. If you enjoyed this article, it would mean a lot if you gave it a clap, shared it, and connected with me on Twitter! You can also subscribe to watch or listen to my podcast!

What Post Scarcity Means was originally published in Hacker Noon on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the views of Bitcoin Insider. Every investment and trading move involves risk - this is especially true for cryptocurrencies given their volatility. We strongly advise our readers to conduct their own research when making a decision.