Latest news about Bitcoin and all cryptocurrencies. Your daily crypto news habit.

The Golden Gate Bridge going into the fog — © Joan Gamell 2019

The Golden Gate Bridge going into the fog — © Joan Gamell 2019

We are at a peak in the tech industry: we are paid more than ever before, most of us get equity while valuations are at an all-time-high (unless you work at Uber or Lyft) — and many get ridiculous perks. This is not normal. This was not the case some years ago, but we have a very limited memory and get used to the good stuff quickly. This is specially true for newcomers to the industry who just got their first job and think it has always been like this.

Thus, it’s in our best interest to take stock of our situation and realize that it’s a product of the demand of technical talent being much higher than its supply. That’s it, pure and simple. It’s not because we are better or special, we, “techies”, just happen to have the right skills at the right time, and there is absolutely no guarantee that this will go on forever. This realization lead me to reflect about what can we do to hedge ourselves against possible worst times ahead. This article is the result.

I hope these words of temperance reach some of the 22-year-old, oat-milk-drinking kids making $120K plus equity in their first job after college for whom the prospect of losing their job is anything but impossible.

When you worry about this minutiae, you don’t have actual problems — @overheardsanfrancisco

When you worry about this minutiae, you don’t have actual problems — @overheardsanfrancisco

Don’t get me wrong, I do think that tech is the future and that the industry will do well in the long run, but no one knows what will happen before we get there. Tweaking and adapting your mindset now — when times are good — will proof savvy if things go south, just like it’s a good idea to prepare for an earthquake, even when you’re not hoping for one to happen.

Taming our insatiable crave for more

We humans have an exceptional capacity to adapt to the circumstances of our environment in a process called hedonic adaptation. That’s why we keep falling for thoughts like “when I get that [car/promotion/job], I’ll finally be happy”, failing to see that when and if we get it, we will adapt to the better circumstances and take that new state as our new baseline for happiness.

But it gets worse: it’s much easier to upgrade — i.e. adapt to better circumstances — (a raise, a better house, a better commute) than downgrade. Practically speaking, the hedonic treadmill spins only one-way, so we better think twice before we spin it.

“I wanted a billion dollars. It’s staggering to think that in the course of five years, I’d gone from being thrilled at my first bonus — $40,000 — to being disappointed when, my second year at the hedge fund, I was paid “only” $1.5 million.”

— Sam Polk, from “For the Love of Money” article in the NYT

This is not a new problem by any stretch. Philosophers have been grappling with this problem for thousands of years and recent psychological studies confirmed it’s an actual phenomenon.

The Stoic Philosophers recommend a technique called negative visualization to overcome this inherent adaptation to the pleasures of life and actually appreciate what we already have (emphasis mine):

“Around the world and throughout the millennia, those who have thought carefully about the workings of desire have recognized this — that the easiest way for us to gain happiness is to learn how to want the things we already have. […]

The stoics […] recommended that we spend time imagining that we have lost the things we value — that our wife has left us, our car was stolen, or we lost our job. Doing this, the Stoics thought, will make us value our wife, our car, and our job more than we otherwise would.”

— William Braxton Irvine. “A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy.”

Some people think negative visualization is eerie because they think people who practice it are pessimists or that they are “calling for bad things to happen”. I don’t think that’s the case. For me, the realization that what you have (including your life) is ephemeral and that it might go away at any time makes me appreciate the present and the things I have so much more than if I just thought they’ll be there forever.

Know what you can control, and what you can’t

Taking the Stoic line of reasoning a little bit further, it follows that we make our happiness more robust the less we tie it to things outside of our control. Take your job, for example, we certainly control many factors that influence our employment: what we study, the companies we interview at, how much initiative we display, etc. But the reality is that we are far from in control — just ask anyone who has been laid off recently.

Nassim Taleb contrasts the hidden risks that employees have with the volatility but visible risks of Artisans:

“Artisans, say, taxi drivers, prostitutes (a very, very old profession), carpenters, plumbers, tailors, and dentists, have some volatility in their income but they are rather robust to a minor professional Black Swan, one that would bring their income to a complete halt. Their risks are visible. Not so with employees, who have no volatility, but can be surprised to see their income going to zero after a phone call from the personnel department. Employees’ risks are hidden.”

— Nassim Nicholas Taleb. “Antifragile”

While Taleb’s point is very valid, not everyone can be or wants to be an Artisan. What can we do then?

Think of your fears, imagine the worse happens — again, negative visualization — then triage what can you do to hedge or prepare against what you can’t control. Focus on what you can control and work on it: learn that new language or skill, start having a side gig as a freelancer, start eating healthier. Whatever it is, it’s better than doing nothing and worrying about what you can’t control.

If your fears come true you’ll be as ready as you can be, and if they don’t, you’ll feel at peace knowing that you are more prepared than most, shall the worse happen.

Live below your means and adapt slowly

Living below your means minimizes the misery you’ll experience if you have to retreat to a lower standard of living in the future. It will also allow you to build up some savings you can tap into to maintain your lifestyle if bad times come.

No one knows how long the party will last in tech. It may last one more year or it may keep going on until we retire. Either way, the worst you can do is expect the party will go on forever and live beyond your means.

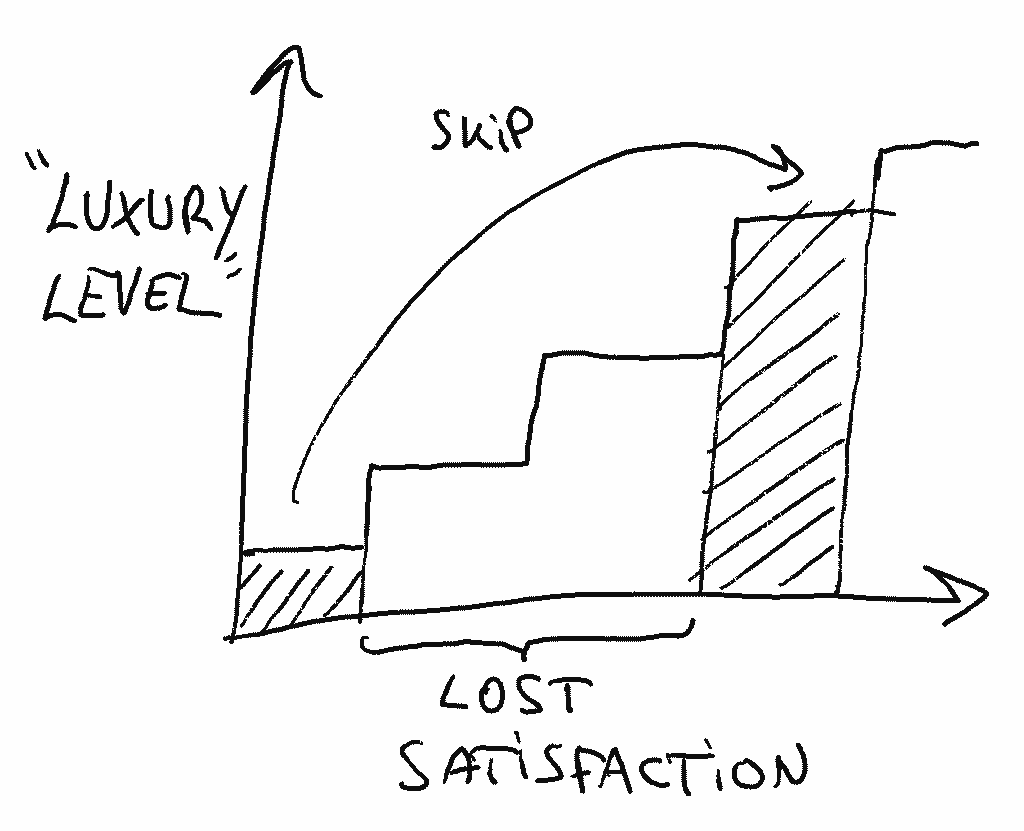

If you want to optimize even more, to derive maximum “satisfaction” from the same amount of cash, try to adapt to a better financial situation slowly instead of all at once. In other words, advance the hedonic treadmill slowly and without skipping any step: Instead of buying that Lambo the second you cash out your RSUs or your crypto, spend that money gradually in smaller, incremental things.

Actually, it’s even better if you spend on experiences: maybe a slightly more luxurious trip than the last one, or start frequenting better restaurants every now and then, you should even try giving some of the money away — the satisfaction we get by helping others is much more lasting than the one we get from material possessions.

Or even better, don’t spend it, save it!

Again, we will eventually adapt to the best of circumstances and this adaptation is mostly one-way, so if you jump from the bottom of a hierarchy (Honda Civic) all the way to the top (Lamborghini) you are skipping a bunch of “satisfaction” to be enjoyed. In nerdy terms, the satisfaction we derive from the sum of visiting all levels of a “luxury hierarchy” is greater than the one we get if we skip any levels.

I hope you enjoy my awful handwriting

I hope you enjoy my awful handwriting

Choose your reference point wisely

TL;DR: Don’t count your RSUs before they hatch

It’s very easy to subconsciously account for your equity and bonus as guaranteed, given that even recruiters include those in the Total Compensation — implicitly assuming that stock prices and the market context will stay stable (or go up!) until your options or RSUs vest.

There is one big catch though: equity and bonus are far from guaranteed to keep their value, they are very much variable (yes, even in public companies). Assuming they are as good as cash has only psychological downside. Daniel Kahneman and Amos Taversky taught us as much with Prospect Theory, which tells us that we tend to evaluate things in terms of gains and losses against a reference point (emphasis mine):

“For financial outcomes, the usual reference point is the status quo, but it can also be the outcome that you expect, or perhaps the outcome to which you feel entitled, for example, the raise or bonus that your colleagues receive. Outcomes that are better than the reference points are gains. Below the reference point they are losses.”

— Daniel Kahneman. “Thinking, Fast and Slow”

Not only that, but losses sting more than gains satisfy us. Also, from Kahneman:

“The third principle is loss aversion. When directly compared or weighted against each other, losses loom larger than gains. This asymmetry between the power of positive and negative expectations or experiences has an evolutionary history. Organisms that treat threats as more urgent than opportunities have a better chance to survive and reproduce.”

— Daniel Kahneman. “Thinking, Fast and Slow”

Putting those two together: given the same payoff we can feel good or (very) bad about it depending on what reference point we initially chose. Imagine you just signed an offer with a privately held transportation startup that includes equity valued at $500k. At that point in time you have two choices: as the startup is set to lead one of the biggest IPOs in history soon, you can mentally account for those $500k (or more!) as if they were already yours, or you could make a conscious effort to try to “forget” about that money, as it’s just illiquid paper money.

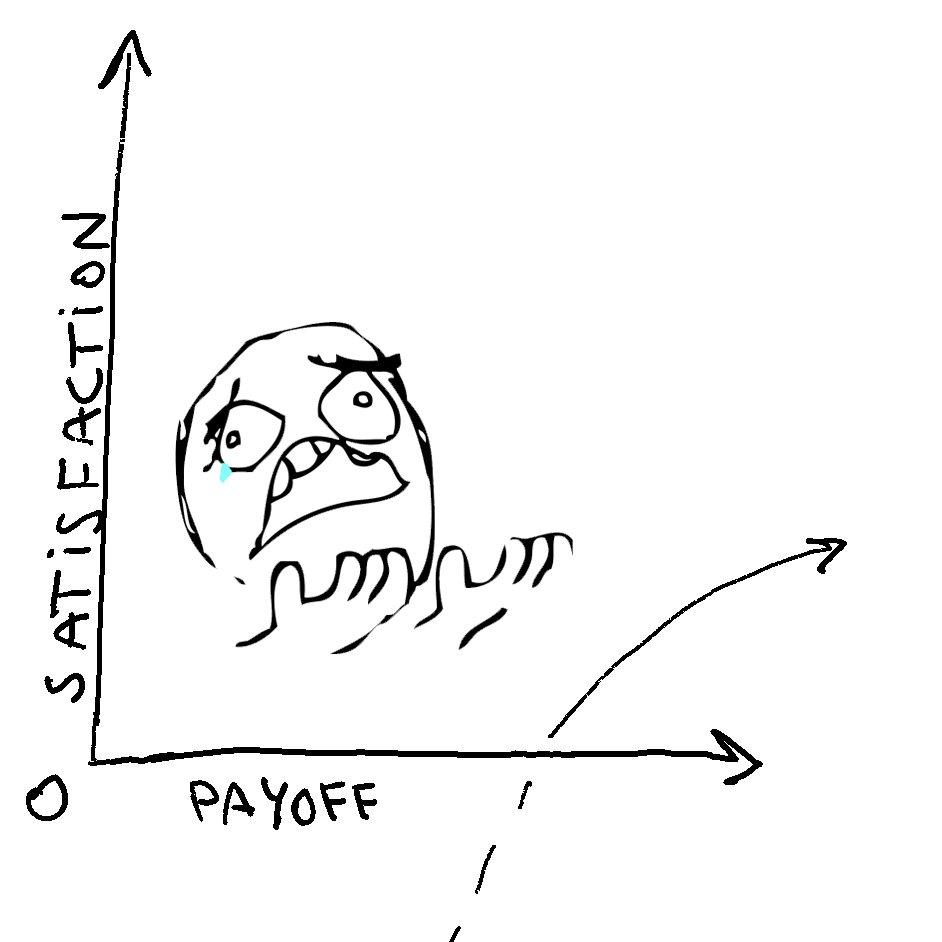

If you don’t make the mental effort to delete the equity from your mental accounting and go the easy path down to assuming you are already $500k wealthier, you will probably feel pretty miserable when, 3 years later, you experience a perceived loss of $200k when the company IPOs and your stocks are “only” worth $300k (before taxes!).

tears of why, or how some Uber employees must be feeling right now

tears of why, or how some Uber employees must be feeling right now

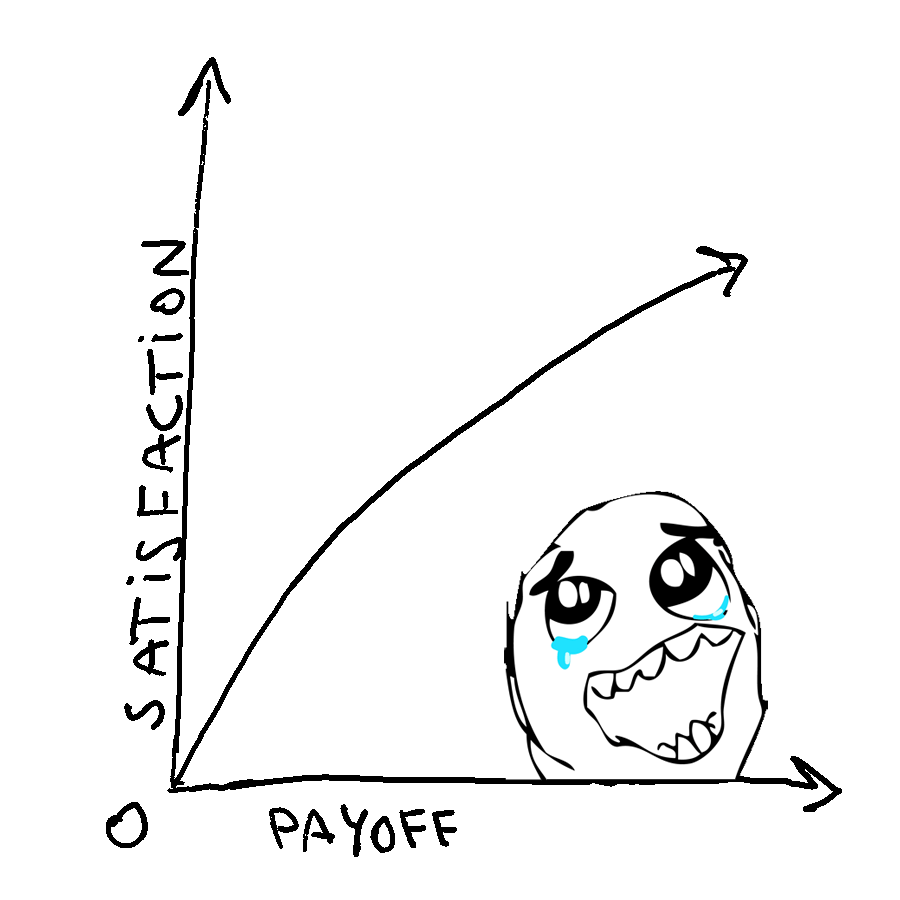

On the other hand, if you had never accounted for that money, the same situation would feel like a $300k gain. Note that the outcome is exactly the same: you are $300k wealthier, the only difference is that you consciously chose the reference point to be zero — expect nothing. Ok, it’s not as easy as it sounds and you can never completely forget about a huge chunk of paper money, but doing the effort will go a long way towards increasing your satisfaction when the payoff comes.

downside completely hedged by setting reference point to 0 — tears of win

downside completely hedged by setting reference point to 0 — tears of win

Sniff for smells

Some might wonder what brought me to write this article, so I will close with some open-ended questions you can reflect on. The same way we look for code smells in our programs, I like to find and ponder on “reality smells” to keep a healthy level of skepticism. Just like code smells, they are not proof that something is necessarily amiss, but I think it doesn’t hurt to reflect on them for a minute.

- It’s been more than 10 years since the last recession: Is this normal? How long have been expansive cycles in the past? Are there any early signs of a recession coming? Can the economy go up forever?

- Is it normal that people ditch their other careers to migrate to tech in droves? Is it sustainable? Will the demand of tech workers keep up with the supply?

- Is it normal that a burned down, derelict house in the bay area sold for almost $1M?

- Can economists and politicians reliably predict recessions?

- Do we think that the future will be more similar to the present than it will actually be?

Don’t Get Used to The Good Times in Tech, They Might Not Last was originally published in Hacker Noon on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the views of Bitcoin Insider. Every investment and trading move involves risk - this is especially true for cryptocurrencies given their volatility. We strongly advise our readers to conduct their own research when making a decision.