Latest news about Bitcoin and all cryptocurrencies. Your daily crypto news habit.

Bradley Tusk envisions a future where politicians lead for the majority of people, rather than just those who make it to polling places. Tusk, who advised several high-growth startups such as Uber, Lemonade, and Eaze on politics and regulation is a major proponent of mobile voting for local and national elections, and he thinks blockchain can help make it a reality.

In the past decade, there have been several initiatives to encourage people to vote, most of which ended up being only marginally effective. Many attribute low voter turnout, particularly that of local elections, to apathy. However, enabling Americans to cast their votes with a smartphone may change that.

Blockchain-powered mobile voting may be on the horizon. If we ever reach it, we may end up living in a world that caters to everyone capable of voting, not just those who actually go to their local stinky library to bubble in their ballot on dead trees.

Many organizations exploring mobile voting have turned to blockchain. Blockchain offers the tangible tracking and identification verification many mobile voting skeptics are rightfully wary about, but most projects focusing on digital voting with the use of blockchain technology are poorly funded and at a lack of active supporters.

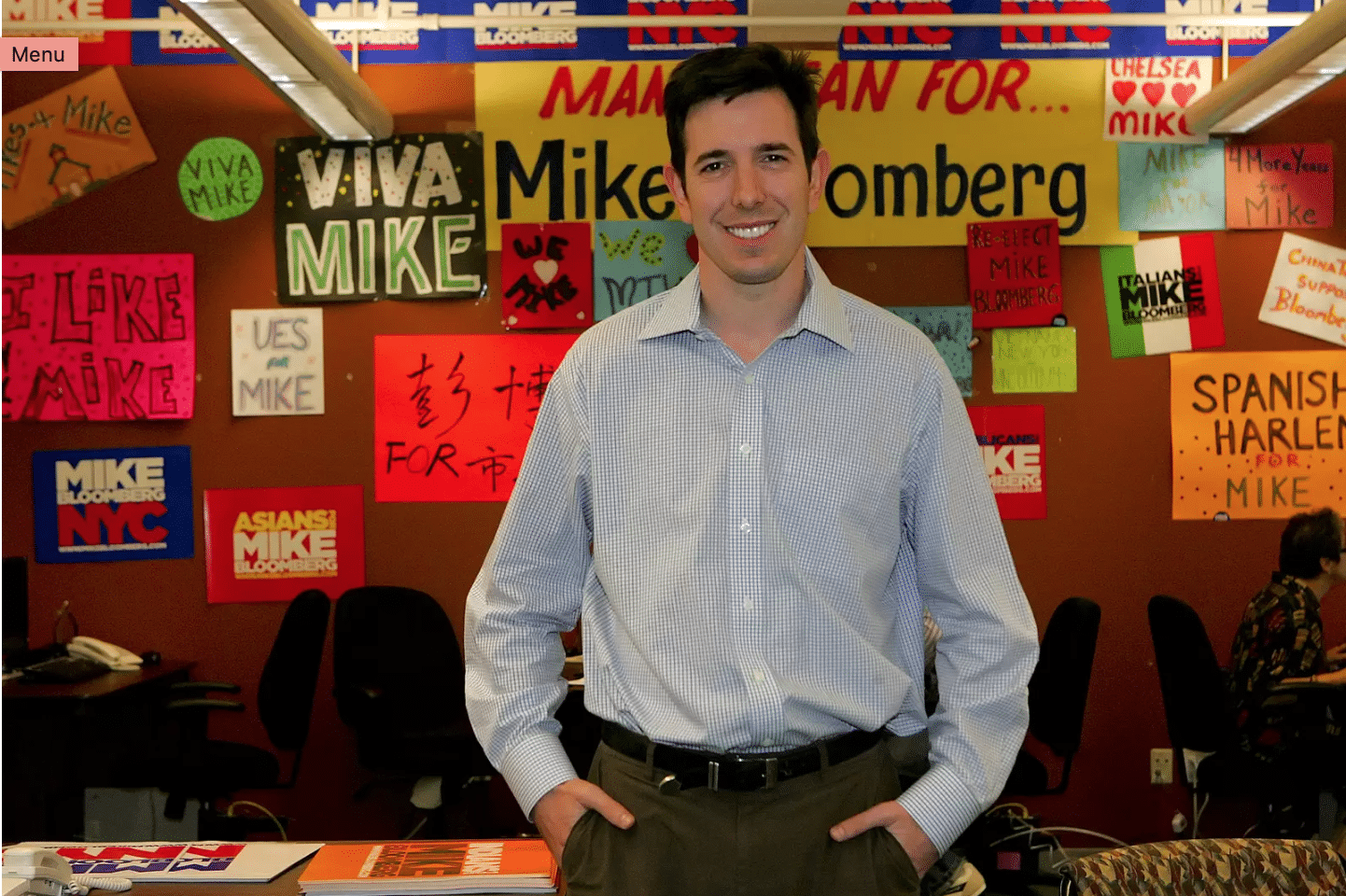

A young(er) Bradley Tusk. Photograph by Ruby Washington — The New York Times/Redux

Enter Bradley Tusk. Tusk spent his twenties and early thirties in high-level political positions such as the Communications Director for US Senator Chuck Schumer, Deputy Governor of Illinois, and campaign manager for New York City tech billionaire Michael Bloomberg’s 2009 successful re-election campaign.

Tusk, often applauded for his meticulous organization and ability to get things done in often stagnated political environments, brought his talents to the corporate and tech space by founding Tusk Strategies in 2011, a political consulting firm that has helped companies like Google, Walmart, and Uber run massive multi-jurisdictional campaigns.

Tusk recounts his political and entrepreneurial life in his 2018 book The Fixer: My Adventures Saving Startups from Death by Politics notes that he “fell into tech by accident” when Travis Kalanick, the founder of a small (at the time) transportation startup named Uber, called asking for strategic guidance and help in fighting the taxi industry in New York City. As Uber’s first political advisor, Tusk helped Uber win its disputes in New York City and similar conflicts around the United States.

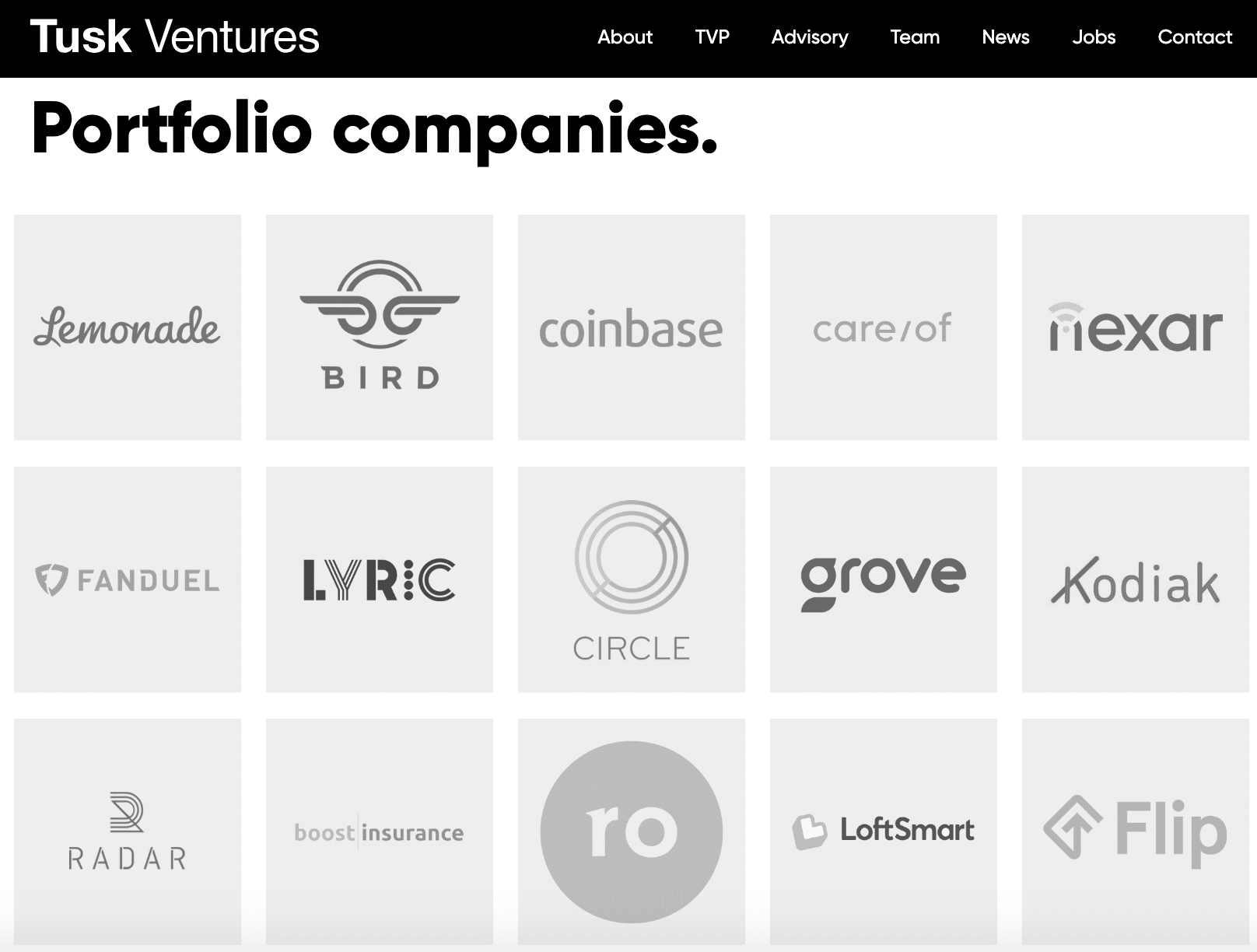

Tusk operates Tusk Ventures, where he provides political, regulatory, and media guidance to high-stakes startups, investing in some on occasion. In addition to Uber, Tusk has helped many top-tier startups avoid death by politics in the sake of disruption. The list includes:

- FanDuel and DraftKings (legalizing online daily fantasy sports),

- Lemonade (big insurance and fighting the strict New York Department of Financial Services to win an insurance license)

- Eaze (making it simple, safer, and legal to get on-demand marijuana in select areas)

- Bird (the myriad of issues plaguing the on-demand scooter industry)

- Handy (in navigating the distinction between contractor and full-time employees)

- Care/Of (in compliantly marketing the company via influencers)

- Ripple (one of our beloved cryptocurrency industry’s darlings/devils)

If a high-performing startup gets embroiled in an existentially threatening sticky political situation, chances are Tusk gets a call.

The Tusk Ventures Portfolio as of 5/9/2019.

I got the chance to speak with Tusk in his New York office and discuss his thoughts on blockchain-based voting, the uphill battle ahead for cryptocurrency projects, and what startups can do to succeed in inhospitable political climates. The following article focuses on mobile and blockchain-based voting.

Mobile Voting: Unleashing the Masses in Action

Tusk’s affinity for mobile voting is likely rooted in his successful 2015 strategy for Uber. Uber faced a proposed bill in New York City that would cap its growth rate to 1% per year in the city – basically a sleeper hold on a high-growth startup.

Uber had two million customers in New York City, many of which much preferred Ubers to what they viewed as the outdated, unsafe, and often discriminating taxi cabs. Tusk’s team decided to mobilize Uber’s user base from within the app.

Photo: Spencer Platt (Getty)

Whenever a user opened Uber in New York City, a popup would quickly explain the issue and make it easy for them to advocate for Uber seamlessly. There was even a “de Blasio” option (idea credited to Kaitlin Durkosh) named after the city’s mayor Bill de Blasio, which if selected, showed people a twenty-five minute wait time and explained the problem. Then, it would ask users to email and tweet at their councilmembers to oppose the bill. Within a single week, 250,000 people did – roughly 10% of Uber’s NYC userbase.

The in-app information, combined with an aggressive advertising campaign that poked at the strings the taxi owners were pulling on the city government, put city hall in a vice.

Tusk was able to alchemize Uber’s massive user base into a political instrument that created ruckus not only for mayor Bill de Blasio, but also the surrounding representatives, officials, and 51 member city council that would be voting on Uber’s future. Representatives from city hall eventually agreed to drop the bill if Uber ended its campaign, which registered as a tremendous landmark success for Uber and Tusk Strategies.

Tusk also employed a similar strategy in a national campaign to help fantasy sports betting platforms FanDuel and DraftKings mobilize their 5 million customers (in the United States and Canada) by sending them geotargeted popups with their state senator and state reps, stating whether their stance on fantasy sports was good or bad. If a state rep in a small county that is used to 60,000 people voting sees 40,000 new people registering to vote just because they want fantasy sports, they’re likely to try to appeal to them.

Bringing Mobile Voting to the Masses

Bradley Tusk helped startups like Uber, Fanduel, and Draftkings jump over the hurdles of the entrenched interests of politicians, lobbyists, and corporations, and good old fashioned political gridlock.

Given Tusk’s prior political involvement, first-hand accounts of political corruption and stagnation (after all, he worked with Rod Blagojevich at one point), and ability to demonstrate the effectiveness of mobile voting for the interests of startups, it’s no shocker he’s a huge advocate for mobile voting.

“All of Uber’s users had smartphones, all we had to do is engage and mobilize them to keep the service they love using,” Tusk comments. “Mobile voting brings the election to where the people are, instead of demanding they go to local polls to have a say.”

Along with his wife Harper Montgomery, Tusk founded Tusk Montgomery Philanthropies, a foundation with a mission to create a reliable and efficient way to vote with your phone.

Mobile voting is a powerful concept for two data-backed reasons:

- It’s estimated that 80% to 95% of all adults in the United States own cellphones, 68% of them smartphones in 2015. Most people are tethered to their smartphones all day, using them for an increasing amount of needs such as banking, transportation, and even dating. Voting from your pocket isn’t nearly as foreign a concept as it was two decades ago, let when our voting laws were created in the 18th century.

- Voter turnout in presidential elections has hovered around 55% since 1960. However, if you’ve been anywhere near social media platforms around election time, people don’t shut up about politics. Social media has helped stimulate and engage millions of people in political conversation. With 169.5 million people using Facebook in the United States (about 52% of the population), there is almost an equal population using Facebook regularly as there is that votes. Sure, this statistic includes many people who can’t vote (age, felonies, etc.,) but that doesn’t take away from how large a slice of the U.S. population (particularly the younger portion of it) is somewhat comfortable, if not immersed, in tech.

The case for mobile voting heats up even more when scoping local elections, where the per-vote impact of every person is much higher, but voter turnouts are pitiful.

For example, in the 2013 Democratic primary for mayor in New York City, only 691,000 out of 8.5 million people voted, 282,000 of them for the winner Bill de Blasi, who would later win the race with 8% of the total population’s vote. Essentially, it took 3.3% of New York City’s voting population to elect the mayor of the financial capital of the world and home to one of the most diverse communities in the world. Tusk was able to mobilize 250,000 people to oppose de Blasio’s Uber-antagonistic bill with a single app feature.

Low voter turnout doesn’t necessarily make any winning politician a villain. It just means the system is broken and can be manipulated. Someone who is elected by a small percentage is going to run operations to try to benefit that percentage, if not the total amount of people that vote at polls. And 100% of a city’s population? Well, their voices simply aren’t as loud unless they’re on penciled in on a ballot. After all, the game for most politicians isn’t to be good in office – it’s to stay in office.

Justin Merriman Getty Images

Tusk, along with many Americans disillusioned with the current American political system, is eager to explore mobile voting to change things. “The idea isn’t to get rid of the old ballot-box system,” comments Tusk. “It’s to utilize modern technology to expand our democracy and incentivize our leaders to lead for the majority instead of a small few people that actually filled out a ballot.”

Estonia, for example, has allowed its citizens to cast ballots from a computer with an Internet connection anywhere in the world since 2005, and the government claims 30% of Estonia’s estimated 1.3 million people use the system to cast votes electronically.

The United States has a history of very close elections, which usually end enmeshed in scandal in this writer’s lovely and totally never dysfunctional birthplace of Broward County, Florida.

Mobile voting, in its lofty ideals of precision, rapid tracking, and tamper-proofing, would encourage more people to vote. For the abysmally low voter turnout in local elections, mobile voting would be a gamechanger for underrepresented populations.

Additionally, the technological preferences of voting demographics will look much different in a few election cycles. If anecdotal evidence is of any value here, we Millennials might be either very opinionated or politically apathetic, but as a unit we are generally too busy, lazy, or distracted to go out and vote in a local election, unless of course there’s some level of social media clout in the form of a trendy I Voted sticker. The verdict is still out on whether Gen Z will survive its mumble rap and Tidepod-eating phase, but it tends to be even more hooked on smartphones than Millennials.

If the option to vote via smartphone were available, chances are voter turnout numbers would be bolstered by younger crowds, and politicians would need to find a way to cater to the needs of the voters rather than lobbyists and campaign funders.

In an interview with The New Yorker, Tusk said “We’re working with these guys to help us get it right. But my view is less that the greatest threat to our democracy is the risk of hacking. The greatest threat to our democracy is that nobody votes.”

The Current State of Blockchain Voting

The frontrunners of the blockchain voting initiative are inevitably going to be the projects implementing their products as opposed to just blowing hot air in the form of whitepapers.

Today’s executions of blockchain voting companies seem fairly paltry in the scope of national elections, but they are worth noting.

Voatz seems to be ahead of its lackluster pack of competitors in taking charge to spearhead blockchain voting. Voatz raised a $2.2 million seed round led by Medici Ventures, which is a wholly owned subsidiary of Overstock.com (see tZero.)

The project’s blockchain-based voting system was recently implemented in West Virginia, primarily to enable military personnel and ordinary citizens to vote using their phones. Tusk Montgomery funded the small pilot with $150,000. In the 2018 primary election, two of the state’s 55 counties used Voatz and only 13 people cast their vote using the system. In the 2018 midterm election, the number of counties offering Voatz voting grew to 24 and nearly 150 people voted – about an 11.5x growth rate in just a few months.

Voatz was also used in Denver, Colorado’s municipal election on May 7th, 2019.

Agora, another blockchain voting company, is also sometimes referenced in the mobile voting discussion. Agora’s site claims its digital voting protocol was partially deployed in Sierra Leone as an International Observer to run a study showcasing blockchain for voting. The site continues to note that the voting protocol was “partially deployed to record votes from a sample of polling stations on an immutable blockchain ledger,” leading to results that provided accurate results from the studied areas days ahead of the manual tally processes.

However, the case study link to “Access the Results” goes to a “Not Secure” site Chrome warning, and then sends the searcher to an Italian hotel’s website. This is one of the more popular projects exploring blockchain voting, something that needs to be as airtight, transparent, and secure as possible.

The company also found itself in hot water after what CEO Leo Grammar called a “bout of miscommunication and a few PR mistakes made on our behalf.” Agora essentially exaggerated the project’s role, claiming the entire election was run on blockchain as opposed to simply just being a concurrent study on a limited sample size, akin to that of a science fair project.

Other projects in the space include Votem, Democracy Earth, Follow My Vote, and Boulé, which currently appear to be rudimentary concepts with landing pages promoting the blockchain voting concept as opposed to bona fide projects politicians (or journalists) can sink their teeth into.

Blockchain Voting’s Long Road Ahead

Every movement has its pioneers. Mobile voting has enormous implications for the United States and the rest of the world, but it’s also a precarious journey littered with booby traps and hostility.

Fighting the Old Guard as a Poor Orphan Baby

Many blockchain-voting companies are enlisting in an incredibly steep uphill battle, operating from mostly empty coffers and vague schemes for monetization.

First off, no politician who has spent their life mastering the art of raising campaign money, getting elected, and staying in office is likely willing to welcome something as fundamentally ground shaking as having millions of people that usually don’t vote to start voting from their phone. Not only will the incumbent politicians be throwing their careers into the tides of fate, but they’ll also be giving a technological advantage to a new wave of politicians capable of engaging and mobilizing new hordes of voters.

Congress doing Congress things. Alex Wong/Getty Images

“Those who like things the way they are – in other words, every current politician, interest group, union, major donors, and anyone else who has no interest in making it easier for people to challenge their power – will raise a host of objections to mobile voting,” Tusk writes in his book.

Second, it’s going to take an enormous amount of resources to go about tackling the establishment, especially with its stockpiles of campaign money, taxpayer money, and deep connections with people that have mastered the inside and outside game of politics. Additionally, battling the established voting processes isn’t as simple as attacking a single fortified castle; it means waging war on thousands of strongholds across state lines. While the governments of the thousands of states and cities might have different priorities, they still march under a single tune.

“[Mass mobile voting is] going to mean changing laws in each state to allow for mobile voting, developing a model set of election rules, policies, and procedures that can be adapted for each jurisdiction, finding a few jurisdictions willing to conduct a pilot program to give the idea a try, and convincing major social platforms, as well as the device developers themselves, to help out by constantly reminding their users to vote,” notes Tusk.

A lack of good monetization options reduces a project’s access to funding from investors, and altruism alone likely isn’t enough to uproot one of the strongest political systems of all time.

The Blockchain Voting Manipulation Argument

It’s not a stretch to assume a two-party political system with a shady history with gerrymandering, corruption, voter intimidation, manipulation via media (and recently social media), and ballot stuffing won’t have masters of the political dark arts find ways to manipulate mobile or blockchain-based voting.

The blockchain itself may be immutable, but there are still many points of failure that could be exploited in a variety of its use cases. The exploitation itself isn’t so unnerving, because let’s face it, political strategists have had a few centuries to find ways to outsmart the current political system. What is unsettling, however, is if a mobile voting system were compromised, it would be done so at scale and likely hard to detect until too late.

The “What if Quantum Computing Derails Our Political System?” Argument

Quantum computing, often referred to as the “crypto killer,” is a looming existential threat that would render blockchain-based voting useless. Quantum computers are able to perform calculations that would otherwise be theoretically impossible for today’s computers in a reasonable time frame, which means anything from molecule simulation (quantum chemistry means potentially finding cures for diseases within days rather than years or decades), logistics optimizations, and cracking cryptographic codes.

Bitcoin, for example, is incredibly stable under current computing, but quantum computing would crack it like Humpy Dumpty, who legend has it once sat on a great wall and had a great fall. A traditional computer today would need to perform 340,282,366,920,938,463,463,374,607,431,768,211,456 basic operations to derive a Bitcoin private key from a public address, or 340 undecillion (340 billion billion billion billion).

Using Shor’s algorithm, a significantly large quantum computer would need just about 2,097,152 operations to crack a private key, a much more manageable number than a one with the word “billion” four times in its name.

Many high-powered quantum computers are still years away. However, the argument that utilizing a blockchain-based e-voting system as a primary voting method of our democratic system takes a stern gut punch by quantum doomsayers. Whether quantum computing will pose a threat to the quantum-resistant blockchain projects, the idea alone is confusing and techy enough to spin into an anti-blockchain voting campaign.

Final Thoughts – Building a Mobile Voting Foundation for the Future

The theory of digital voting with the use of blockchain technology seems to be picking support, but it is going to have trouble materializing without adequate talent and capital to bring it to life.

However, this is just the case for today. Americans likely aren’t going to be convinced to support something that already sounds confusing and too techy to elect our leaders, especially if our only data points are thirteen people using blockchain to vote with their phones in West Virginia.

But, that’s exactly what these projects are right now – data points. “This is probably a ten- to twenty-year project, and it’s going to mean having rock-solid answers to […] concerns about hacking, especially as concerns about foreign interference in U.S. elections via Facebook, Google, and Twitter only grow,” Tusk wrote in his book and reinforced in our conversation. “The more instances we have of successful blockchain-based mobile voting, the better the argument for it will be in the future.”

We likely won’t see mobile voting or voting on the blockchain in upcoming national elections, but for now, it’s about collecting data points that demonstrate that it is feasible. If anything, today’s successful blockchain-voting projects will serve as much-needed ammunition for future generations that will take the torch of liberty and ignite the path between our archaic political system and the technology of tomorrow.

Featured image by Buck Ennis

The post Uber’s First Political Advisor Looks to Tackle Mobile Voting with Blockchain appeared first on CoinCentral.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the views of Bitcoin Insider. Every investment and trading move involves risk - this is especially true for cryptocurrencies given their volatility. We strongly advise our readers to conduct their own research when making a decision.