Latest news about Bitcoin and all cryptocurrencies. Your daily crypto news habit.

How to build the product you want to and not go out of business

Programming notes: this post is n in a series of indeterminate length on Product topics mainly for startup people, mainly leadership, mainly coming from non-GTM backgrounds. There’s a list at the end.

Vision and Distraction

Spirits professionals will tell you that takes significant up front capital and reserves in the bank to wait out the many years it takes [barrel aging!] before you have a good product.

Note: A terrible product is easy to come by in a few months. That might work for some market for some of the time, but eventually those brands are low-margin loss-leaders in bigger portfolios or they have severely limited growth or they go under.

So what do we do in the meantime? We make gin.

On the way to making whiskey, some of our product can be made into gin — which is sellable at a hefty enough margin to keep things humming along while the intended project is sitting in barrels maturing, finding its character. [No offense to gin and gin-lovers!]

Example!

Here’s Kottke repeating Michael Wolfe regarding Uber [notes in brackets mine]:

If you think of Uber as a town car company operating in a few cities, it is not big. [Gin.]

If you think of Uber as dominating and even growing the town car market in dozens of cities, it gets bigger. (Data point: there are now more Uber black cars in San Francisco than there were ALL black cars before Uber started). [Gin.]

If you think of Uber as absorbing the taxi markets, it gets pretty huge. [Gin.]

[…]

If you think of Uber as a giant supercomputer orchestrating the delivery of millions of people and items all over the world (the Cisco of the physical world), you get what could be one of the largest companies in the world. [Whiskey.]

A fairly common thing for founding teams is to get distracted at some intermediary step, settling for a smaller market, or getting trapped chasing early revenue and use cases that don’t lead to their ultimate goals.

Which is not necessarily bad! It can be a perfectly legit business and life decision to pivot into something that we find on the way to building the Next Big Thing.

Strategy and Models

How do we make keep ourselves on track? How do we know we’re building what we intended to build, solve the problem we intended to solve, serving the user we intended to serve?

Arguably, that’s what a roadmap is for, but those rarely go beyond the near-term and get progressively fuzzier as you go further out in time.

Note: Roadmaps are good! We still need a roadmap of some kind to organize our product development week over week over month over quarter etc.

We need some kind of product strategy, which amounts to goals and principles of decision making to achieve those goals:

- What is the core problem we are trying to solve?

- Who are the people we want to help?

- How do we think that translates into a product?

- How does that break down into the smallest components that create and provide value?

- What are the possible paths and order of composition from nothing to the product that includes those components?

- What are we not building? What, or who, will we say no to?

- Can we test each thing we build against our go to market (GTM) model — i.e. will it help us stay alive: market better, sell more, achieve the next round of funding, etc?

- Does each thing we build advance us towards our vision?

Note: Any product strategy lives in the context of some market and, hopefully, a business strategy. A product strategy != business strategy. For that you need goals and principles for marketing + sales + distribution + product + operations + cashflow.

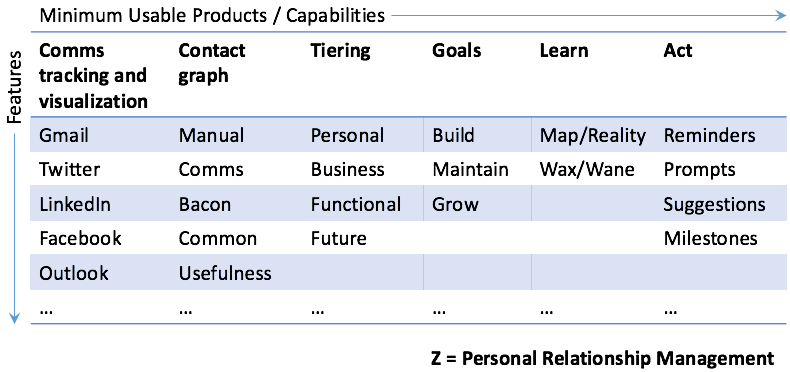

Here is one model. Like all models, it’s both wrong and also useful.

The top left is where we’re starting. Z is the ultimate goal in the form of a product — aka the “product vision” — at the bottom right. [Z should probably be visualized as an additional cell hanging off the bottom right, but that looked odd so ¯\_(ツ)_/¯.]

The columns are features that add up to something. Across the top row is what they add up to: capabilities, or maybe even products, that are in and of themselves valuable. Each of which has to be built on the way to building Z.

The bar for something belonging in the leading row is being a minimum usable produc (MUP), which is a subset of capabilities needed for Z. It should also be minimally go to market viable (MVP!), meaning someone would pay for it. Hopefully those are the same thing. If they’re not, we gotta reconsider our theories about the world that led us here.

Note: Yes, I’m using MVP weirdly since anyone actually being willing to pay for your MVP isn’t generally a criteria as the term is used.. which is funny if you think about “viability” having any meaning..

We could go very deep in each column and build a maximally (?) usable product. That’s a business decision more than anything else. We should draw a line at some depth in each column showing where the MUP ends and more-polished-product begins.

Questions to ask

- Is the minimum usable depth we project actually sufficient for the intended user to experience value?

- Is the minimum usable depth sufficient to get the product to the point of go-to-market viability — we can market, sell, and close business against it? If not, how much further?

- Is going deeper than that worthwhile for the customer or the business?

- Are these the best capabilities in the best order?

The ideal case is to get to something in each column that provides enough tangible value and positive experience that someone would pay for it. This serves to provide market validation of the direction we’re moving in and potentially provides an option of building a run rate business on top of which to continue towards our ultimate vision.

Any path that moves us closer to Z is good and valid. Any path that doesn’t, or takes us off the road to Z entirely is bad and invalid. This is the stuff of company-wide teeth-gnashing.

Example!

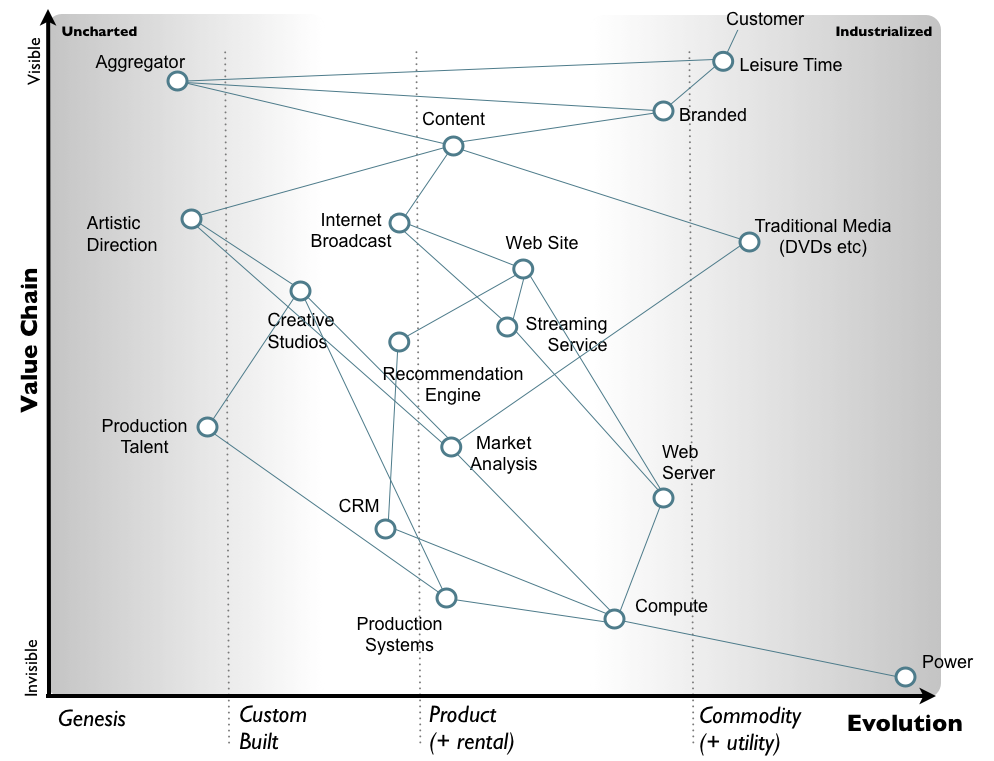

A good way to fix our product strategy in the context of the competitive dynamics of a particular market and it’s value chain explicitly is to use a Wardley Map.

This is not for the faint of heart. See the reading list below for pointers.

Example!

Any given product or feature should do one of two things:

- Increase an existing revenue stream: add features that deepen value for an existing use case

- Create a new revenue stream: going broader by adding new use cases, or features needed for a new channel.

If anything on the roadmap doesn’t fulfill one of these goals — it gets binned.

Note: Maintenance, bugfixing, paying down technical debt, and cost optimizations are all arguably about maintaining or improving existing revenue streams.

Everything is a hypothesis

Going to market is the sensing mechanism that tests our hypotheses — if no one will pay for it (or give us money to build it), then we can’t live to build another day.

Final Note

We can always go deeper and/or broader.

And we can stop where we are, discard everything that we though would follow, in order to build a new vision to a new place.

But that new place has to be reachable from where we are right now. Every thing we build closes some doors and opens others. It’s near impossible to do something completely discontinuous.

What we build today limits what we can build tomorrow.

Posts in this series

- Product 101 for Engineers

- Product 102 for Engineers

- Minimum Usable Product

- Product, Marketing, and the Art of Managing Expectations

Reading List

- Simon Wardley’s OSCON 2015 Keynote: Situation Normal, Everything Must Change

- Simon Wardley: Introduction to Value Chain Mapping

- Eugene Wei: Invisible Asymptotes

- Ben Thompson: Stratechery

- Me: AWS Lambda — a lesson in using product strategically

- Me: Marketing 101 for Engineers

- Me: Marketing 102 for Engineers

- Me: Sales 101 for Engineers

Product 102 for Engineers: Decision Making and Strategy was originally published in Hacker Noon on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the views of Bitcoin Insider. Every investment and trading move involves risk - this is especially true for cryptocurrencies given their volatility. We strongly advise our readers to conduct their own research when making a decision.