Latest news about Bitcoin and all cryptocurrencies. Your daily crypto news habit.

Julia is a comparably new language that aimed to have the performance of C and simplicity of Python. Having the ability to perform data analysis without much trouble while shipping the code with competitive performance, Julia is expected to be a powerful tool in FinTech businesses. But I think it also have some great potentials regarding to the current trends in Cybersecurity.

Julia, Image from Medium

Julia, Image from Medium

In this article, I will explain why Julia can also be a great tool for the future of Cybersecurity. Meanwhile, I will share how I wrote a Julia script on my Mac computer to crack a cipher text encrypted with Caesar Code Shift and Columnar Transposition. In the end, I will share some performance comparisons and the code for this project in the appendix.

Cryptography, from Caesar Code Shift to Biometric Authentication

First let’s review some of the basics in cybersecurity. How we encrypt our messages and authenticate users. We will go over the old school Caesar code shift and columnar transposition, which are involved in the code example. And then, we will go over biometric authentication and why Julia can be a great tool for the future of cybersecurity.

Caesar Code Shift & Columnar Transposition

As human we communicate with each other, but sometimes we do not want everyone to know what we are communicating about. Since Ancient Rome Julius Caesar have been sending secret military messages by shifting code letters in the message. For example “A” will be shifted to “B” and “Z” will be shifted to “A”. The word “HAL” will be shifted into “IBM”. The technique was later on named after him, known as the Caesar Cipher.

A Caesar cipher disk, image from Wikipedia

A Caesar cipher disk, image from Wikipedia

There was a huge vulnerability to such code-shift based encryption. During the early time of the second world war, the mathematicians analyzed the frequency of occurrence of each alphabet in Germany. By comparing the frequency bar charts, they were able to figure out the shift. The story extends to how the Germans then invented the Enigma, and how Alan Turing managed to crack it with his giant computing machine.

There were many other techniques we used to encrypt our messages. Another one is the columnar transposition. Which involves putting the text into a table, then rearrange the columns and read the text back.

Other encryption methods such as RSA, ECC, and MD5 are widely used in sending information securely over the internet. RSA for example, is an Asymmetric Encryption taking advantage of the properties of prime numbers.

Biometrical Authentication & Artificial Intelligence

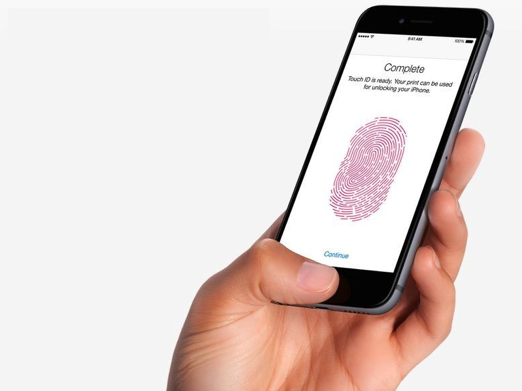

The first time our ancestors utilizes Biometrical Authentication is probably way earlier than they started playing with code shifts. People distinguishes each other by looking at their different faces. Fingerprints for another example, is widely used as a credential for a person. The technology companies later on uses it to provide a simple and fast user experience in device authentication. For example, the Touch ID on an iPhone.

Touch ID illustrated, image from Cult of Mac

Touch ID illustrated, image from Cult of Mac

As a sub-branch of Human Computer Interaction, Biometric Analysis is widely used in various applications. It has been a known trend that there will be more artificial intelligence applied in the field of human computer interaction, which is widely encouraged in related conferences. From my survey over hundreds of publications, Machine Learning, Computer Vision and Data Analysis have been proven to have great impact to the field of Biometric Authentication. Data Science and Artificial Intelligence will become a useful tool in Cybersecurity on both the defender side and the attacker side.

Why Julia Matters?

As a language designed for Data Science, Machine Learning and other popular technologies, Julia made research easier while not sacrificing performances by a lot. It is a language designed for us to ship our fancy data science algorithms without having to rewrite them on another language.

Julia is a powerful tool for Data Science and Machine Learning

Julia is a powerful tool for Data Science and Machine Learning

As the increasing involvement of data science and artificial intelligence in cybersecurity, which also requires a good performance in its related applications, Julia definitely comes to be a handy fit. Want to lean about how it works? Let us go over an example right away!

Cracking Caesar Code Shift and Columnar Transposition with Julia

KUHPVIBQKVOSHWHXBPOFUXHRPVLLDDWVOSKWPREDDVVIDWQRBHBGLLBBPKQUNRVOHQEIRLWOKKRDD

I was asked to decipher the above cipher text. The hint was it was ciphered with Caesar Code Shift and Columnar Transposition with a key length shorter than 10. Deciphering those secret messages generally involves some kind of brute force approach, which can be computationally expensive. In order to reduce some of its complexity, collision with dictionaries is also necessary.

To make it fast, the first thing that came to my mind was C. But those headers and memory management can be a pain to deal with. Python on the other hand, is supported by powerful libraries and minimalistic grammar, but sacrifices lots of speed. After some considerations, I end up doing it with Julia.

1. Getting Started

Now Let us get started!

First, we will have to download Julia, a Mac version of the download can be found here. You can also visit the official download page for other versions and info.

After the download, we can open the command line console by double clicking on the application icon.

Opening Julia’s Command Line Console

Opening Julia’s Command Line Console

To run any scripts saved as local file, we can use the include() command inside the command line console:

include("<PATH_TO_YOUR_JULIA_SCRIPT>/hello_world.jl")The name of the file has the extension .jl.

Now in order to complete this project, we will also need to import two packages:

- The Combinatorics which we will need to generate the permutation for the columnar transposition

- The ProgressMeter which we will need to show the deciphering progress.

We can do so with the following commands.

Installing Combinatorics:

#import Pkg; Pkg.add("Combinatorics")Installing ProgressMeter:

import Pkg; Pkg.add("ProgressMeter")We also need a dictionary file which can be downloaded from here. The dictionary contains commonly used English words which we can use in the future to collide with our cipher text.

2. Importing Cipher Text and English Word Frequency

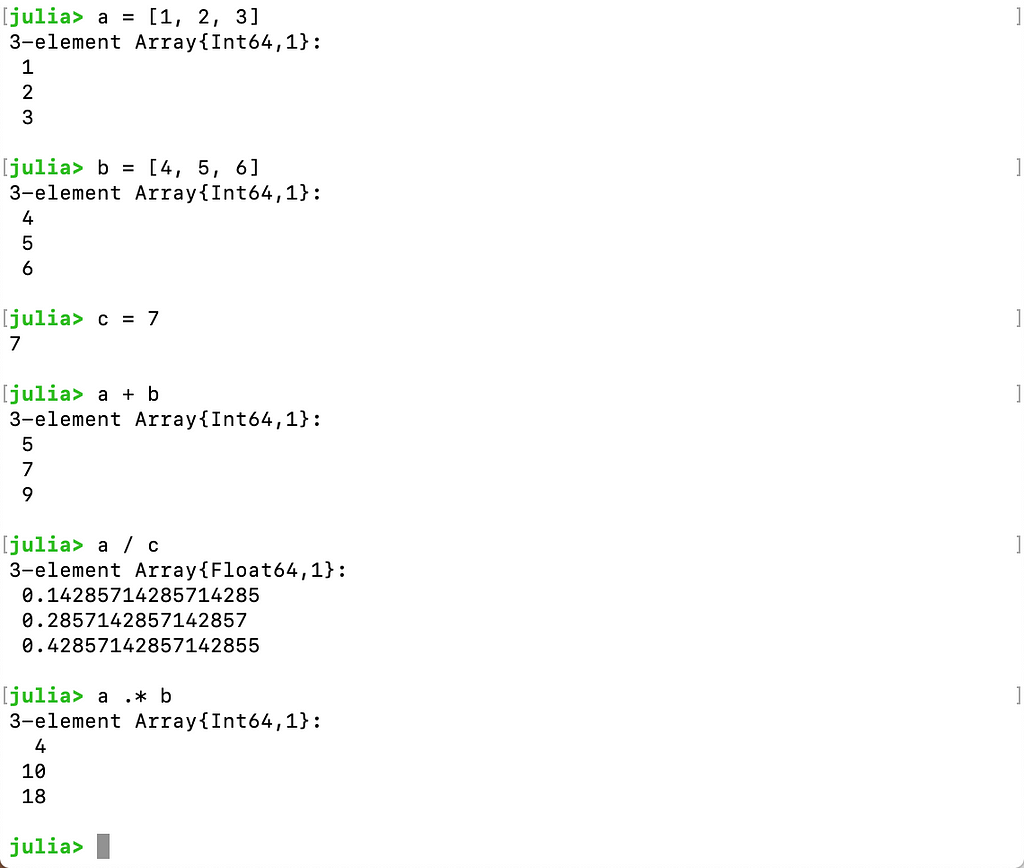

We can define a string in Julia just like in any other languages, and we do not need to specify the type. The println() function prints the string to a new line like many other languages such as Java. The strings are concatenated with a comma instead of a plus symbol.

cipherText = "KUHPVIBQKVOSHWHXBPOFUXHRPVLLDDWVOSKWPREDDVVIDWQRBHBGLLBBPKQUNRVOHQEIRLWOKKRDD"println("Begin to decrypt cipher text: ", cipherText)Each letters occurs at different frequency in English, where a list can be found here. Different sources may have slightly different statistics. We can define a list of floating points in Julia with the following command.

println("Initializing frequency array for ENGLISH...")ENGLISH = [0.0749, 0.0129, 0.0354, 0.0362, 0.1400, 0.0218, 0.0174, 0.0422, 0.0665, 0.0027, 0.0047, 0.0357, 0.0339, 0.0674, 0.0737, 0.0243, 0.0026, 0.0614, 0.0695, 0.0985, 0.0300, 0.0116, 0.0169, 0.0028, 0.0164, 0.0004]Now we would like to count each of the letters, so we have to create a list of zeroes with the same size as there are alphabets in English. We can do so with the following commands. The length of the lists can be retrieved with length(). We can cast a character to integer with Int(). The values can be incremented with a “+=” operator. A for loop in Julia looks like the following:

counts = zeros(length(ENGLISH))for letter in cipherText code = Int(letter) - Int('A') if code < 1 code += 26 end counts[code] += 1endWe do as many shifts as there are alphabets in the english language, totaling 26 shifts including no shifts. We can do so with the circshift() function.

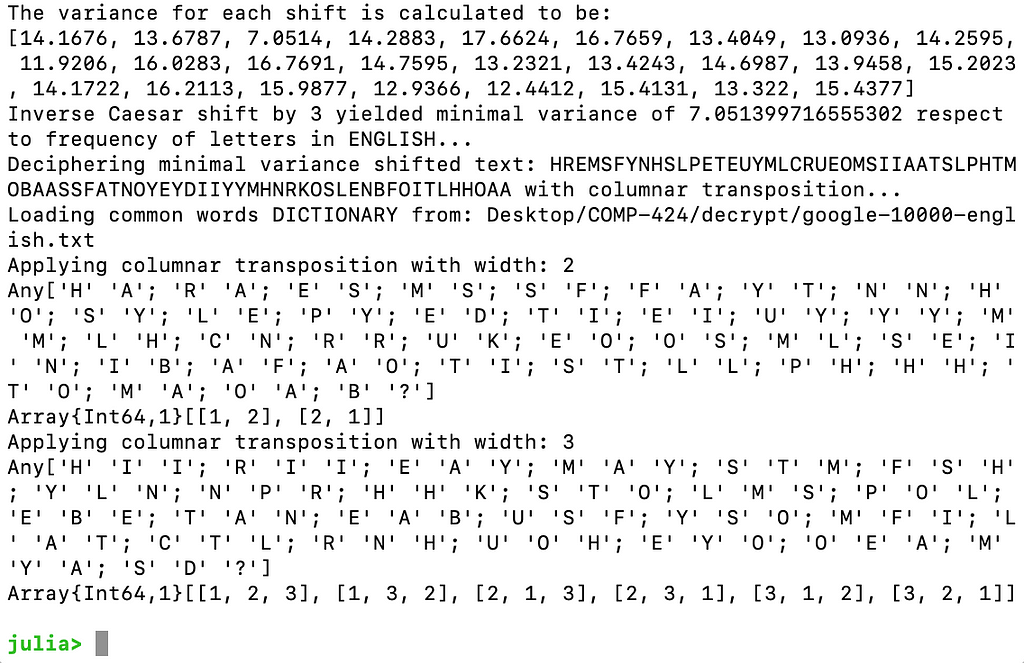

variances = zeros(length(ENGLISH))for shift in 0:length(ENGLISH) - 1 println("Applying inverse caesar shift: ", shift) shiftedCounts = circshift(counts, -1 * shift) variance = sum(broadcast(abs, ((shiftedCounts / length(cipherText) - ENGLISH) / ENGLISH))) variances[shift + 1] = variance;endprintln("The variance for each shift is calculated to be: \n", variances)minshift = argmin(variances)Inside the for loop we calculate the difference between the counted frequencies and their frequencies in English words for each alphabet. Subtractions and divisions can be done directly at list level. The function boardcast() maps the abs() function to each elements inside the list similar to Scheme or Java Script. The sum() function finds the total sum of the list. The variance for each letter is divided by their frequencies in English so the variance is not influenced by how frequent the letter appears.

variance = sum(broadcast(abs, ((counts / length(cipherText) - ENGLISH) / ENGLISH)))

The list operations work similar to Python, while “.*” is used for multiplication. Features such as subtraction of an integer from an array is not yet supported. More information can be found in the official documentation.

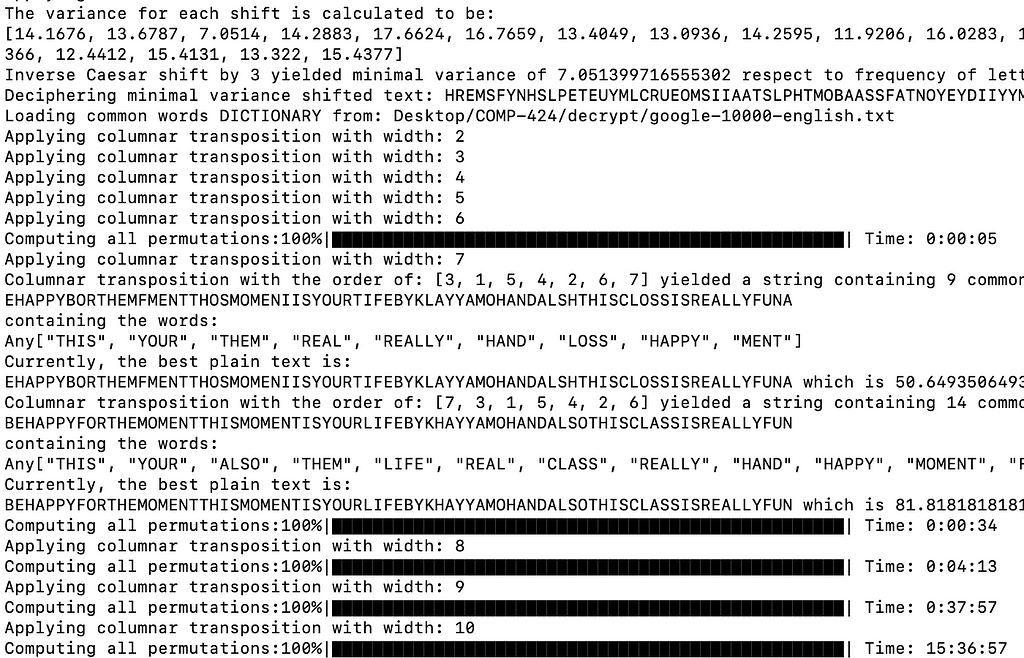

Now if we run the code, we should get the following, the program figured that the most plausible shift is 3.

Now we can print the shifted string with the following scripts. The Char() function casts the integer code back to a character, the append!() function appends the character to the list, and the join() function joins the character list into a string.

shiftedTextList = []for letter in cipherText code = Int(letter) - minshift if code < Int('A') code += 26 end append!(shiftedTextList, Char(code))endshiftedText = join(shiftedTextList)println("Deciphering minimal variance shifted text: ", shiftedText, " with columnar transposition...") Most Plausible Shift String Printed3. Applying Columnar Transposition & Utilizing Dictionary Collision

Most Plausible Shift String Printed3. Applying Columnar Transposition & Utilizing Dictionary Collision

First, we have to reference the necessary packages we installed in the previous sections, we can do so with the following codes. These declarations can be put anywhere before they are used rather than having to be at the top of your code.

using Combinatoricsusing ProgressMeter

And then we can import our dictionary with the following code.

filename = "<PATH_TO_YOUR_DICTIONARY_FILE>/google-10000-english.txt"println("Loading common words DICTIONARY from: ", filename)DICTIONARY = readlines(filename)This should print a snippet of the dictionary after we save and run the code.

Loading Dictionary File In Julia

Loading Dictionary File In Julia

Now we want to construct the column matrix and iterate through each of the permutations. The following code will do the job.

for width in 2:3 println("Applying columnar transposition with width: ", width) matrix = [] height = Int(ceil(length(shiftedText) / width)) total = width * height for index in 1:total if index <= length(shiftedText) append!(matrix, shiftedText[index]) else append!(matrix, "?") end end matrix = reshape(matrix, (height, width)) orders = collect(permutations(collect(1:width))) println(matrix) println(orders)endThe ceil() function rounds up the number to the closest integer. We fill the blank spaces with “?”. The reshape() function shapes the matrix to the specified dimensions. We generate the orders with permutations(), which takes a list of elements as input and returns all the possible permutations. The input is generated with collect(1:width), where collect converts the “1:width” range into a collection, in other words a list.

Now after save and reload we should see the reconstructed columnar tables printed with the permutations. Semicolons indicates a new row.

Columnar Tables and Permutations printed in Julia

Columnar Tables and Permutations printed in Julia

Before we go through the permutations, we should display a progress bar as the task is going to take some time. We do not want to sit and wonder whether the program is still running or not. With the packages we have imported, the following code before the loop will initialize the progress bar.

n = length(orders)p = Progress(n, 1, "Computing all permutations:", 50, :black)

And we put this in the end of the loop to update the progress bar. For more info on how to use the ProgressMeter, take a look at here.

next!(p)

The complete code for dictionary collision can be found below. Where it uses uppercase() to capitalize the words in the dictionary, and occursin() to see if it appears in the rearranged text. Once the common words contributed to a significant amount of the rearranged text, it prints them out and keeps track of the permutation yielding the highest percentage of common words.

completed = 0n = length(orders)p = Progress(n, 1, "Computing all permutations:", 50, :black)bestPlainText = "?"bestPlainTextCommonPercentage = 0for permutation in orders plainTextMatrix = [] for row in 1:height for columnIndex in 1:width char = matrix[row, permutation[columnIndex]] if char != '?' append!(plainTextMatrix, char) end end end plainText = join(plainTextMatrix) wordCount = 0 wordLengthSum = 0 words = [] for word in DICTIONARY if length(uppercase(word)) > 3 && occursin(uppercase(word), plainText) wordCount += 1; wordLengthSum += length(word) push!(words, uppercase(word)) end end percentageCommon = wordLengthSum / length(plainText) * 100 if percentageCommon > 50 println("\rColumnar transposition with the order of: ", permutation, " yielded a string containing ", wordCount, " common word(s) which makes it ", percentageCommon, "% common words, below is the string:\n", plainText, "\ncontaining the words:\n", words) if percentageCommon > bestPlainTextCommonPercentage bestPlainText = plainText bestPlainTextCommonPercentage = percentageCommon end println("Currently, the best plain text is:\n", bestPlainText, " which is ", bestPlainTextCommonPercentage, "% common words...") end next!(p)endThis algorithm is not perfect, where the percentage has the potential to go over 100% if there are overlapping words. Making it perfect takes a bit too much work as you have to consider all the word permutations, so let us stick with the quick and dirty way for now. The percentage is also here just for the reference.

Before we go for the test, we also have to increase the maximum width of the table to 10, as we know that to be the maximum length of the key from our hints.

We change:

for width in 2:3

into:

for width in 2:10

And we should remove the following test code we had before:

println(matrix)println(orders)

Now we should be able to save and launch the code.

Deciphering with Julia Scripts

Deciphering with Julia Scripts

And after some time, we should see the plain text getting printed as it has the highest percentage of common words. The text is deciphered to be:

BEHAPPYFORTHEMOMENTTHISMOMENTISYOURLIFEBYKHAYYAMOHANDALSOTHISCLASSISREALLYFUN

Julia Script Successfully Decrypted the Text

Julia Script Successfully Decrypted the Text

Congratulations!!! You have just learned how to write a cipher text cracker in Julia! Hope this to be a great start of your exploration in the language.

In the end…

Julia is a simple and powerful language in data analysis. You can read more about its performance from the links below:

- Basic Comparison of Python, Julia, Matlab, IDL and Java (2018 Edition)

- Basic Comparison of Python, Julia, R, Matlab and IDL

- A Speed Comparison Of C, Julia, Python, Numba, and Cython on LU Factorization

You will see that the performance of Julia goes way ahead over Python for larger input sizes, and even surpasses C for matrix calculations. Matrix calculations are widely used in machine learning and data science, and the input size can generally become really large.

I am a passionate coder who loves learning new things and share it with the community. If there are anything particular you would like to read please let me know. I mainly focus on Artificial Intelligence, Human Computer Interactions and Robotics right now, but there are lots of things I can write about.

I can continue write on Julia and maybe a little bit on Data Science. Many of my research works are confidential but once they are released, I will have lots to share. I can also re-create data science models in Julia, just like how I coded an Artificial Neural Network in Unity C# before their machine learning modules are well built. Hope you enjoyed learning these cool new stuffs as much as I did!

I have attached the complete code of this project to the appendix.

Appendix (Complete Code of this Project):

My code finished all the permutations after a total of 16 hours:

Julia: a Language for the Future of Cybersecurity was originally published in Hacker Noon on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the views of Bitcoin Insider. Every investment and trading move involves risk - this is especially true for cryptocurrencies given their volatility. We strongly advise our readers to conduct their own research when making a decision.