Latest news about Bitcoin and all cryptocurrencies. Your daily crypto news habit.

As our interest in cryptonomics deepens, we’ve started thinking about different crypto value propositions. This applies to individual coins or tokens — such as, what is the intrinsic worth or valuation of this or that crypto instrument?

But crypto valuation analysis also extends to broader metrics of worth, such as the strength of a core developer network, the development status of various level 2 projects, a given network’s posture in ongoing governance debates, and so on.

As analysis moves from superficial indicators of worth (like price), towards the valuation of certain intangible assets (like a blockchain project’s IP), one sees that crypto valuation today is far more art than it is science.

Crypto market capitalization analysis says far less about the underlying crypto project(s) under review and far more about the vision and/or limitations of the crypto-economic methodology that’s being applied by a given analyst.

In effort to make crypto valuation more robust, we propose that the budding field of cryptoeconomics adopt a metric of the overall value added to the current global economy by crypto: Gross Crypto Product (GCP).

What is Gross Crypto Product?

As an economic measure, our conception of Gross Crypto Product (GCP) is expressly modeled on Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the monetary value of final goods and services — that are bought by the final user — produced in a country in a given period of time (say a quarter or a year).

Extending the metric to crypto, here’s one possible definition:

Gross Crypto Product (GCP) is the monetary value of final goods and services — that are bought by the final user — produced using crypto instruments, networks, and/or assets in a country in a given period of time (say a quarter or a year).

Immediately, the proposed metric can be attacked as overbroad and/or too narrow. Among other reasons, the proposed metric is overbroad because country-wide analysis fails to differentiate value being generated on particular networks. The metric is too narrow and fragmented because information networks produce maximum value at global scales; thus, a country-by-country GCP methodology would fail to capture the true global economic impact of crypto.

These critiques are well taken. But they are not unique to this proposed crypto economic measure. The same methodological and empirical problems exist in GDP measurement as well. This is why we have measures like nominal GDP, GDP per capita PPP, and why we have competing GDP measurement methodologies.

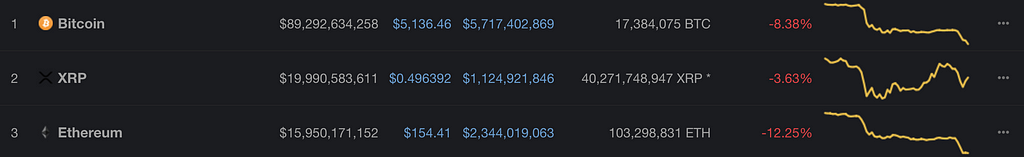

A map of world economies by size of GDP (nominal) in USD, World Bank (2014) (Source: Wikipedia)

A map of world economies by size of GDP (nominal) in USD, World Bank (2014) (Source: Wikipedia)

Our hope for crypto is that competing GCP methodologies emerge as well. Hence, our definition of GCP is not meant to be exclusive or preemptive. We need other definitions and methodologies, and look forward to helping develop them.

For instance, although we advance GCP on a per-country basis, we do so as a heuristic device, because that’s how GDP is traditionally defined. Our analysis shows that country-specific methodologies would be most useful for country-specific policy deliberations and/or comparative regulatory analysis. But far better models are possible and desirable for different analytical needs.

Why Have a GCP?

As a measure of economic value, GCP helps us understand the real impact of crypto economic activities. This is useful for many ongoing debates, such as:

- environmentalist critiques of crypto

- ongoing crypto regulatory debates

- ongoing blockchain governance debates

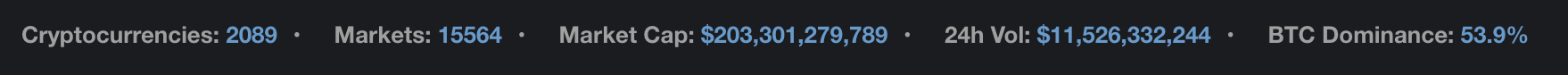

The basic reason we need more complex valuation models is that valuation pegged to market capitalization for individual crypto coins or tokens — or even total market capitalization — fails to adequately capture the reality of the crypto economy. Here’s a screenshot from Coinmarketcap.com from October 31, 2018:

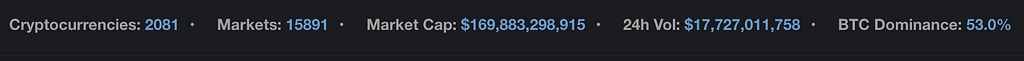

Here’s a screenshot on Monday, November 19, 2018:

Crude price modeling would suggest that some thing or things happened in these intervening three weeks that wiped out $30B+ of overall crypto value.

Did something like that happen? Not really. The crypto world was in the midst of its usual turbulent news cycle. Some big stories from this time frame that could explain a downturn were things like the SEC’s announcement of a settlement with the creator of a decentralized Ethereum-based exchange — EtherDelta. Additionally, Bitcoin Cash (BCH) underwent a hard fork, splitting the coin in two.

On the plus side of the valuation ledger, Christine Lagarde (Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund) extended an open invitation to crypto to essentially create global public-private partnerships. As far as crypto news go, this is as encouraging and legitimating a development as it gets — and yet, if we look at price action, the story is radically different.

So, better quantitative metrics of crypto value are possible and desperately needed. These include:

- GCP measures for individual coins (valuation metrics that incorporate market price, but focus on the core economic value of the activity happening on a given blockchain)

- GCP sectoral measures (e.g., (a) total value of goods and services in the crypto decentralized cloud storage market; (b) total value of goods and services produced in the blockchain ‘level 1’ platform (e.g., ‘crypto OS’) market; (c) valuation of different crypto money markets (e.g., CryptoLending, crypto debt collection, et al.), etc.)

- GCP geographic measures (e.g., regional or state-wide assessments, especially for tightly-territorially-regulated coin use cases, like online gambling; this is extremely useful for understanding the effects and potential of crypto vis-a-vis economic development)

- GCP global measures (including models that can serve as functional equivalent to Gross National Product (GNP), a la Gross National Crypto Product (GNCP));

- etc.

Sample GCP Measures

You might be surprised to learn this, but there are several existing attempts to define something like Gross Crypto Product. Right now, there are GCP measures that are very narrowly construed. And there are very broad GCP measures. After surveying these two approaches, we propose a balanced middle path.

GCP, Broadly Construed

The broadest conception of crypto economic outputs that we have come across hails from the Economic Space Agency (ECSA). The ECSA does not use the term GCP in its work (as far as we can tell), but on sum, GCP is precisely what the econauts are trying to model. (‘Econauts’ is what members of the Economic Space Agency collective call themselves.)

The ECSA cryptoeconomic argument is very complex, so we encourage everyone to brew a big pot of tea prior to delving into it. But generally, the key point is that we all benefit from inclusive crypto economic spaces and measures of crypto economic value that go far beyond price.

The key insight developed and deployed by Economic Space Agency theorists is that crypto price is a rather poor indicator of the economic value produced in a given period of time. Price-based analysis is also a very poor predictive analytical tool for understanding the intrinsic value (& potential value) of different crypto instruments.

GCP, Narrowly Construed

The term Gross Crypto Product also has more narrow definitions. In our research, we find the first usage of the term in August 2017 by a crypto trader — hirounsung.

Here’s hirounsung in the hiro’s own words:

Without claiming to have a clear answer, using a different metric to market cap. Instead, using a “gross crypto product”. The GCP would let us understand if crypto is a bubble by how much wealth is created each period. The concept of the GCP lies on the production, which comes from staking, mining, etc. and the price at which these coins are being produced.

Trying to find out the origin of the wealth created by coin creation is the core problem to be solved. For this, we can tell that the basic cost comes from electrical expenses, as well as equipment cost.

Hirounsung’s insight is a brilliant one. We use it above as the basis for our first type of GCP measure: GCP measures for individual coins.

Hirounsung’s framework seems to be focused on the value of the inputs and outputs (as captured in a given crypto instrument’s price & other indicators). The model outlined by hirounsung illustrates the importance of adding the cost of crypto mining inputs, and other inputs for “coin creation.” These metrics are certainly relevant at any scale, but they apply chiefly to mining-based blockchain projects.

As the blockchain space moves increasingly towards different proof-of-stake (POS) and other validation models, GCP measures would need to shift to other estimates of coin cost (such as, perhaps, the operational cost of interest necessary to run validator nodes in a POS environment).

Hirounsung’s framework is a narrow one, but it is useful in particular contexts precisely because it is narrowly tailored.

GCP, Platform Valuation

GCP platform valuation is an alternative middle path between the broad and narrow conceptions of GCP outlined above. The basic valuation question here is: what’s the total value of goods and services produced on, say, the Ethereum network in a given time period (2018)?

Price theorists and market fundamentalists could point to Ethereum’s market capitalization in a given point in time (or average it over a given time frame, like a quarter or year). One answer to the question above is that the value of the Ethereum network is reflected in the market price of Ethereum.

The basic rationale for equating price with value is that “the market” accounts for all of the diverse material and immaterial, subjective and objective, intrinsic and extrinsic factors that weigh into valuation. Thus, today’s roughly $16B market capitalization of Ethereum already factors in things like legal risk (outstanding & potential liabilities), market risk, technical risk, regulatory risk, etc.

Maybe crypto price already captures the full range of on-chain dynamics and off-chain risk factors and market realities. But maybe it doesn’t.

For Ethereum, a crypto platform that has expressly positioned itself as a crypto base layer — something like a technical enabler or incubator for other budding crypto projects — alternative valuation models seem very desirable.

For instance, in real material terms, the economic value of meek @Littercoin, an Ethereum-based blockchain reward for generating geo-spatial data, seems directly relevant to the overall valuation of Ethereum. The same is true for the thousands of other Ethereum-based token schemes that are already generating value globally.

We’re mindful of the difficulty of building valuation methodologies that incorporate market price and also focus on the core economic value of the activity happening on a given blockchain. Asking what is Ethereum GCP is akin to asking what is Ford’s GCP (Gross Car Product = the total value of goods and services produced using Ford cars in a given year). GCP modeling is a big undertaking.

Our intuition is that, in contrast to Ford’s GCP, crypto-platform valuation methodologies can actually be based on rigorous quantitative data.

Tracking the myriad ways in which Fords are used is inherently difficult. Understanding the myriad uses of Ethereum by different — and, often, competing — development teams is also difficult.

But because the whole point of crypto is to keep track of economic activity on robust verifiable ledgers, an Ethereum GCP seems far easier to construct, refine, and optimize than something like a Ford GCP.

Lastly, advancements in blockchain forensic/auditing technologies suggest that complex GCP-like models may already be in use. If so, we hope the developers of these models open them up for public deliberation, peer-review, and improvement.

What’s Next for Gross Crypto Product?

We hope crypto theorists, economists, and crypto accountancies (like Megan Knab’s Veriledger) engage with the Gross Crypto Product idea.

The value of deploying different robust sets of valuation methodologies is that they allow us to understand how crypto contributes to the overall functioning of the global economy. That level of insight seems to be a prerequisite to the development, promulgation, and/or adoption of any global regulatory or governance framework.

Rushing to regulate without stopping to analyze may drastically curtail crypto’s realization of its full potential.

GCP: Gross Crypto Product was originally published in Hacker Noon on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the views of Bitcoin Insider. Every investment and trading move involves risk - this is especially true for cryptocurrencies given their volatility. We strongly advise our readers to conduct their own research when making a decision.