Latest news about Bitcoin and all cryptocurrencies. Your daily crypto news habit.

With thanks to William Hogarth.

With thanks to William Hogarth.

This post is part one of two about venture and venturing. Part One examines the ‘what’ and the ‘why’ of venture, primarily from the perspective of the providers.

Part Two delves into ‘how’ venturing actually works in the context of ‘venture services’, the corner of the venture ecosystem I occupy as a partner of London-based Pivot Venture Services.

This series is also about early-stage startups: what it means to work in and around them and why venture is an investment option worthy of consideration by startup founders.

The header image of this article is from William Hogarth’s series of paintings on fortunes made and lost during the birth of modern capitalism in London. Anyone who works in the startup space today will recognise the cast of hustlers, fantasists and rogues, not to mention the world of opportunity and (above all) risk in which they operate.

What is Venture?

Venture means risk. ‘To venture’ as a verb implies sharing risk in an activity for which the outcome is uncertain. Venturing requires an appetite for risk and chaos. Despite the urge to reduce risk in the context of investment, there is no avoiding the risk profile of venture which remains high when set against other investment options.

When they hear the word ‘venture’, most people think of venture capital. Venture capital firms are integral to the sector we loosely call ‘technology’ and the growth story of almost every ‘tech company’ we can name (and countless others that we can’t).

Despite achieving what feels like mainstream status, venture capital still describes the allocation of funds to very high-risk investments that could potentially offer higher returns. These investments are called startups. Venture capital firms give funding to startups in exchange for equity.

‘Venture’ in this article means the exchange of services for equity in a startup, as opposed to an investment of cash. This form of exchange has commonly been known as ‘sweat equity’ (sometimes simplified to just ‘sweat’) to imply a trade of labour (‘sweat’) rather than capital. Venture is not a separate asset class, but a form of venture capital.

‘Sweat equity’ in software has existed since time immemorial. However, it has usually meant the time invested by the founding team of a startup (for no fee) rather than an arrangement with another company.

Sweat equity agreements have occurred between startups and software services firms, but they have tended to be pro-bono side hustles (“We really like you but you don’t have any money so we’ll do some work for equity”) rather than the strategic focus of the services provider. In the last few years, these relationships have begun to proliferate and evolve.

Venturing, as a theme or business category, has recently received a lot of exposure. Much of this can be attributed to UsTwo’s Jules Erhadt who delivered a ringing endorsement of its future in his widely read article ‘State of the Digital Nation 2020’, subtitled ‘Venture Road’.

‘State 2020’ provides an exceptionally thorough account of the global venture landscape. It reveals a fragmented ecosystem and a diverse range of players. Even the names vary widely. There are startup studios, product studios, venture development firms, venture studios, venture services firms and venture builders. To this list, Jules adds his own twist, the creative capital studio.*

Most venture firms tend to focus on the product and ideation capabilities of the team; hence the frequency of terms like ‘factory’ and ‘studio’ in the names. These reflect the background of the founding team who, as a rule, tend to come from digital strategy, design or engineering backgrounds.

But venture is a two-sided business, services and investment. And, in my experience, the investment challenge is the harder part to get right.

There are many capable services companies from across the agency and development shop spectrum who can deliver good quality software products to agreed schedules. There are very few investment firms that can consistently generate high returns at seed stage.

From what I can see, the underlying economics of venture are rarely disclosed by any of the players. As a result, it’s hard to know exactly how they structure their venture deals, or their historic rates of return. It’s easy to make the case for venture as an exciting business to enter. But a profitable one? Not so much.

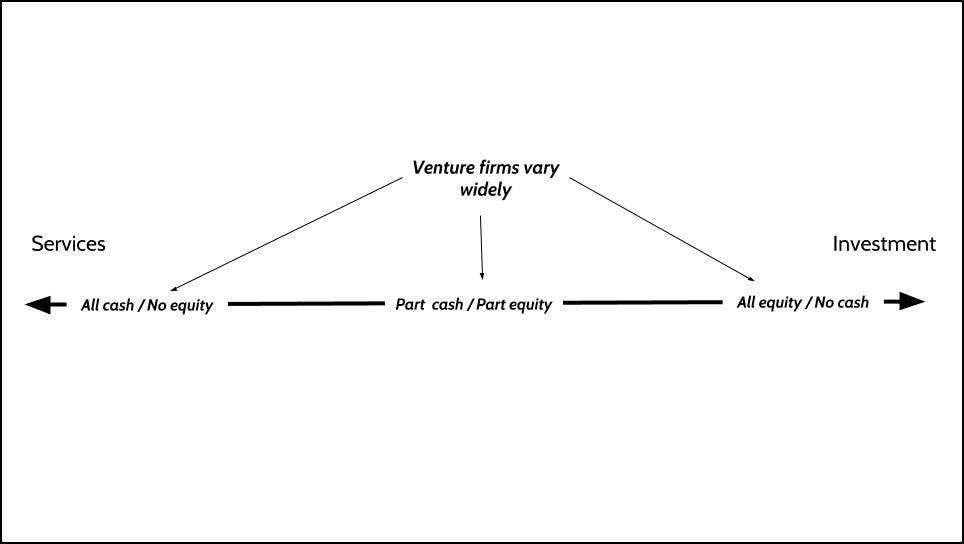

Many venture firms work for both cash and equity. This is because they are discounting their services and do not have a fund of capital to draw on. This arrangement skews towards the ‘services’ end of the spectrum in terms of its value-proposition and the nature of the relationship it engenders.

Those that are funded tend to focus on the potential upside (rather than the short-term benefit of cash) of the deal, so work for equity only. These firms tend to be viewed (and treated) more like investors.

To complicate things further, the spectrum of equity different venture firms expect is also very broad.

For startup studios the amount is typically more than 50% and sometimes upwards of 80%, making CEOs employees rather than founder-owners. For venture services firms, the amount is typically in the 20% ballpark for startups who are pre-product and need an MVP. For startups who have an MVP and some traction, it can be as little as 10%.

Why Venture?

In my experience, people choose to venture for 3 reasons.

The first is that everyone wants to work with startups and build the next cool product.

Unfortunately, startups tend to be closed to outsiders. They don’t engage much with service companies or consultants. They are cash strapped by definition and self sufficient as a result.

The curious only really have to two routes in: found one or join one founded by someone else. Of course, you could invest also in one. But investors don’t ‘work with/in’ their investees and rarely get a glimpse of real life behind the curtain; just the rosy reality founders want to convey.

The second reason is a contributing factor to the first and was well articulated recently by Y Combinator’s Jessica Livingston.

In her article, ‘Think about Equity’, Jessica points out that no one gets (really) rich from earning a salary,

“There’s another way to make money besides salary. You can get it by starting a startup or by going to work for one. And deciding which startup to work for is not like deciding what big company to work for, where you go for the big names, because the equity with the most upside is that of startups so small that most people have never heard of them”.

Most of us have been brought up to associate material progress with salary increase. But, in the last decade, we have observed many young (mainly) men generate incredible wealth for themselves and their colleagues in relatively short periods of time. None of them did so by working for a salary at a large company.

Real wealth is achieved through owning, not earning. The economic landscape in the West is changing and the expectations of the workforce are changing too. People realise that equity is the real source of wealth. And they want in.

Finally, there is economic necessity.

As the subtitle suggests, one of the key themes of State 2020 is that the future of the ‘cash for services’ model employed by digital agencies is bleak. Commoditisation is destroying profit margins and will continue to do so unless they reinvent how they charge for the value they create. The only way forward, according to Jules, is through venturing.

Why is Venture still niche?

If the appeal (and potential upside) of working with startups is so great, why isn’t venturing more widespread? The reason is that successfully combining services with investment is far more challenging than many realise.

To quote Jules (again),

“the economics of risk-based, deferred revenue, venture work is fundamentally irreconcilable with paid for time consultancy work.”

Services companies are cash generative. The cash they receive for their services allows them to pay their only real costs (their staff) and net a healthy profit. Venturing, on the other hand, is investing, which means deferring cash for equity. Equity in private companies is illiquid. As a result, cash flow becomes a problem very quickly for services companies moving into venture.

Funding venture activity from the profits of a services business is unsustainable long term. I have experienced firms all but go bankrupt attempting the transition. Be warned.

Jules is correct in his observation that, without access to a pool of capital (which he refers to as a ‘sidecar fund’), it’s near enough impossible to stay afloat.

How can these two very different business models be reconciled? We will explore this in Part Two.

TL:DR

- Venture means trading services for equity in startups and is a form of venture capital.

- Despite an upsurge of interest in the business model, the venture space is currently diverse and fragmented, with no dominant players.

- Venture remains niche due to the complexity of its business model.

- No comprehensive data exists on the profitability or rate of return across the industry.

*Despite this article’s focus on venturing with startups, it’s important to acknowledge that many of the elite consultancies, notably McKinsey and Boston Consulting Group, have been venturing in the enterprise for some time via their BCG Digital Ventures and McKinsey New Ventures arms.

McKinsey labels this endeavour ‘asset-based consulting’ and, after years in stealth mode, has gradually begun publishing details of its solutions. Not surprisingly, the financial arrangements that underpin the venture deals with their clients remain undisclosed.

On Venturing was originally published in Hacker Noon on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the views of Bitcoin Insider. Every investment and trading move involves risk - this is especially true for cryptocurrencies given their volatility. We strongly advise our readers to conduct their own research when making a decision.