Latest news about Bitcoin and all cryptocurrencies. Your daily crypto news habit.

Facebook has repeatedly shown that it doesn’t care about protecting the privacy or data of its users. Here’s the evidence

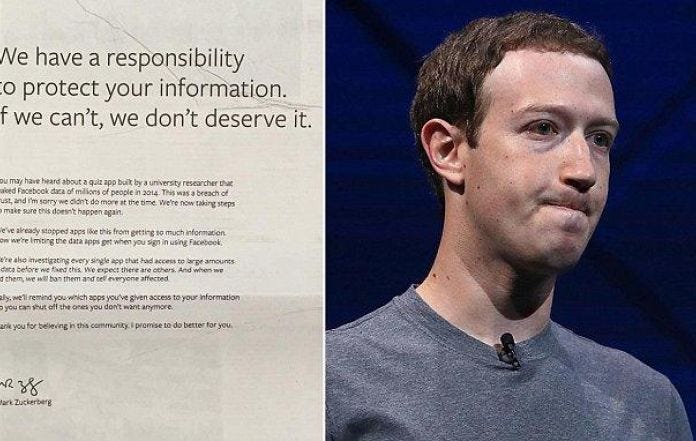

Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Facebook, appears to be in full damage-control mode after recent revelations that Cambridge Analytica accessed the information from 50 million users without their knowledge. On a Facebook post on March 21st, Mark Zuckerberg publicly apologized for the incident, stating that “We have a responsibility to protect your data, and if we can’t then we don’t deserve to serve you…I’ve been working to understand exactly what happened and how to make sure this doesn’t happen again”. He also stated on a CNN Interview, “This was clearly a mistake”. Mark Zuckerberg has also taken out full page ads to publicly apologize in the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, and 6 other UK newspapers.

Despite this apology, and despite claims from Mark Zuckerberg that Facebook will take steps to protect their users’ data from now on, I still continue to believe that neither Mark Zuckerberg nor the rest of the executive team at Facebook truly cares about protecting the data or privacy of its users. Here’s why.

Mark’s apathy towards Facebook’s data privacy begins in 2004, during Facebook’s early days. According to Business Insider, the then 19-year-old Mark Zuckerberg had the following exchange with a friend shortly after launching Facebook (at that time “The Facebook”) from his dorm:

Zuck: Yeah so if you ever need info about anyone at Harvard

Zuck: Just ask.

Zuck: I have over 4,000 emails, pictures, addresses, SNS

[Redacted Friend’s Name]: What? How’d you manage that one?

Zuck: People just submitted it.

Zuck: I don’t know why.

Zuck: They “trust me”

Zuck: Dumb f — ks.

This shows a complete disregard for the data privacy of Facebook’s users from the very beginning. There are several counter-points that could be made to this piece of evidence, along with my arguments against those counter-points:

Counterpoint one: This exchange during Zuckerberg’s college years does not represent the current views that Mark Zuckerberg has towards Facebook users. Mark Zuckerberg’s views have matured since then.

Argument against counterpoint one: It is true that people say and do stupid things during their college years. However, I believe that in general the beliefs that people have are formed during their college years and stay consistent unless there is a massive reason for shift in belief. Due to cognitive dissonance, people generally don’t like information that is contrary to their viewpoint of the world. In this exchange Mark Zuckerberg states “trust me” in quotation marks, implying that Facebook’s users are naive to trust his with their data. The next line where Mark Zuckerberg explicitly insults Facebook’s users is clear evidence of his disregard for people who use Facebook. Do people do stupid things in college? Absolutely. But it’s one thing to get a little too drunk at a college party. It’s another thing to willingly give the information of your website’s several thousand users (who have some expectation of privacy) to your friend for free, and then insult your users and imply they are naive for trusting you.

Counterpoint two: This exchange is fabricated to make Zuckerberg look bad (AKA the “fake news” argument)

Argument against counterpoint two: Neither Mark Zuckerberg nor a spokesperson for Facebook have publicly denied that this exchange took place

Furthermore, in the book The Facebook Effect early Facebook engineering boss and Zuckerberg confidant Charlie Cheever said the following: “I feel Mark doesn’t believe in privacy that much, or at least believes in privacy as a stepping stone. Maybe he’s right, maybe he’s wrong.”

In 2010, the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) and 14 other consumer groups accused Facebook of manipulating “the privacy settings of users and its own privacy policy so that it can take personal information provided by users for a limited purpose and make it widely available for commercial purposes…The company has done this repeatedly and users are becoming increasingly angry and frustrated”. This statement came in response to Facebook’s decision to open up an increasing amount of user’s personal information as public. Facebook’s response was that they were operating within legal parameters.

Counterpoint one: Facebook’s actions were legal

Argument against counterpoint one: Defending unethical actions by essentially stating “It’s fine because it’s legal” isn’t exactly reassuring.

In 2014, it was revealed that Facebook performed a study with a portion of their users to see if it was possible to emotionally manipulate their mood based on what a user sees in their newsfeed. It turns out that yes, it is possible to manipulate people’s mood through what they are shown on Facebook. Engaging in an experiment to manipulate people’s moods without their consent is grossly unethical and a severe violation of trust.

Counterpoint one: Facebook’s data scientists only did this experiment for 0.04% (698,003 people in total) of its users for only one week. Not that big of a deal.

Argument against counterpoint one: The study per se is rather harmless, but it is the implications of what Facebook is capable of that matters. Imagine if Facebook wanted to manipulate a large amount of their user’s emotions without their noticing. They would be capable of doing so. Regardless, even being able to manipulate only 0.04% is a rather big deal depending on what they are manipulating these users to do. It’s been shown that the 2016 election was decided by about 77,000 votes. That’s less than 0.01% of Facebook’s users. That means Facebook (and by extension advertisers that use Facebook) has the ability to swing an election one way or another by manipulating an incredibly miniscule portion of its users.

Counterpoint two: Users agreed to this in Facebook’s Terms of Service agreement.

Argument against counterpoint two: It’s a well known fact that almost no user actually reads those incredibly long Terms of Service agreements, considering they’re written using verbose and impenetrable legalese that even a seasoned lawyer would have difficulty dissecting. I think it’s safe to say that the users of Facebook didn’t expect to agree to be psychologically manipulated when agreeing to its ToS.

Facebook purposely manipulated the moods of its users

Facebook purposely manipulated the moods of its users

In May 2017, a document leak out of Facebook’s Australia office revealed how Facebook executives promoted advertising campaigns that would allow advertisers to exploit the emotional states of its users, with the ability to target people as young as 14 years old. The document initially stated that advertisers can find “moments when young people need a confidence boost.” If that seems innocuous enough, consider the fact that the document also claimed that Facebook can estimate when teens are feeling “worthless,” “insecure,” “defeated,” “anxious,” “silly,” “useless,” “stupid,” “overwhelmed,” “stressed,” and “a failure.” There’s something incredibly Orwellian about allowing advertisers to target teenagers based on their perceived emotional states. The potential negative consequences that could occur, assuming a bad actor were to get ahold of that information, would be endless. No doubt that Facebook allows advertisers to target users based on their political preferences, and that this information was key to Cambridge Analytica.

In March 21, 2018, a twitter user (@dylanmckaynz) reported in a tweet that Facebook had recorded about 2 years’ worth of phone call metadata from his Android phone, including names, phone numbers, and the length of each call made and received.

Counterpoint One: Android users gave Facebook permission to do this as it explicitly requests permission for contacts.

Argument against counterpoint one: This is a perfect example of overly vague terms where users didn’t know what they were agreeing to because they assume that the company has their best interest in mind. I don’t think most people expected that their phone’s metadata would be given to Facebook.

Facebook also bragged in a success story listed on its website that Rick Scott, governor of Florida, used Facebook advertising to increase support from Hispanics. Facebook claimed that the advertising was a “deciding factor in Scott’s re-election”. Another success story listed from Facebook shows how Facebook was pivotal in the Scottish National Party achieving an overwhelming victory in the 2015 UK general election.

Conclusion

The idea that Facebook couldn’t have possibly had an effect on the 2016 election, as Mark Zuckerberg had initially suggested, or that the Cambridge Analytica data breach was some obscure exploit that Facebook couldn’t possibly know about, is absurd. The data gathering tricks that Cambridge Analytica used was an open secret to digital marketers, who have known about this sort of thing for years. Facebook should’ve known about these data-gathering exploits considering they were so widely known. So why didn’t Facebook do anything about these exploits?

The first explanation is that Facebook is grossly incompetent. The second explanation is that Facebook doesn’t really care about protecting the data and the privacy of its users, because its entire business model is selling out user data to advertisers. Considering the intelligence and experience of the Facebook team, I think the second explanation is more likely.

Thank you for reading. Please click and hold the 👏 below, or leave a comment.

I was not paid for this article. If you’d like to support me, you can donate ETH to this address: 0x0BcB78d67D8d929dc03542a5aEdef257f378e513

Facebook Doesn’t Care About Protecting Its Users was originally published in Hacker Noon on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the views of Bitcoin Insider. Every investment and trading move involves risk - this is especially true for cryptocurrencies given their volatility. We strongly advise our readers to conduct their own research when making a decision.