Latest news about Bitcoin and all cryptocurrencies. Your daily crypto news habit.

The history of our benefactor – cryptography – is one filled with intrigue, drama, religion, statecraft, tinkerers, amazing minds, and so much more. In the first of a series, News.Bitcoin.com examines a crypto tale to illustrate its wonderfully colorful development and usage. This particular instalment recounts a 432 year-old plot to kill a queen, and how early forms of cryptography were coveted weapons in the broader battle for Europe’s very soul.

Also read: Massachusetts Censures Five ICO Crypto Startups in a Single Day

Crypto as Life and Death in 1586

A letter meant for Mary Queen of Scots found its way to the desk of Francis Walsingham, England’s preeminent spy master. His charter was to protect the Queen, as in England’s protestant Queen Elizabeth. He was the 16th century’s version of James Bond, if 007 was on steroids.

For the time, rudimentary encryption was something of an arms race. Messages had to be relayed back and forth with the risk of falling into the wrong hands. As such, ever-new and inventive ways to hide their contents were of the utmost importance. Mr. Walsingham was among the first statesmen to recognize encryption’s power, and so a sizeable portion of his budget was allocated to employ coders and code breakers.

A major challenge for all that effort came when the Queen Elizabeth’s cousin, the very Catholic Mary Queen of Scots, was driven out of Scotland. As a way to protect Mary, the protestant Queen Elizabeth offered conditional sanctuary. To appease her protestant base, and the increasingly powerful Mr. Walsingham, Elizabeth placed Mary under a kind of house arrest, fearing her very presence could spark a revolt among England’s Catholics still smarting over what they considered usurpation, believing Mary the nation’s rightful monarch.

By all accounts, for much of her life Mary was a babe: tall, flawless complexion, she often caught the fancy of Catholic noblemen who would pledge their allegiance and devotion. Anthony Babington was among them. He is best described as a country gentleman who, after having met Mary, pledged his life to freeing Mary and restoring Catholicism to England.

Substitution

Mr. Babington dreamed of an outright foreign Catholic invasion of England, assassinating Queen Elizabeth, and freeing Mary. The three-part project was bold, but he soon found collaborators. For any of it to take place, Mr. Babington would have to get Mary’s blessing. The consequence of such an insurrection, even just in its beginning stages, would surely carry a traitor’s gruesome death for himself, his conspirators, and Mary.

In order to alert her of his machinations, Mr. Babington relied on an ancient method of encryption: substitution. As much as two thousand years ago, ancients knew to split the alphabet, forming pairs, allowing for simple encryption. Each letter would automatically trigger another, potentially frustrating an interceptor. The method was advanced to include substituting symbols for letters, as in the Pigpen cipher, which uses shapes surrounding letters. In fact, the substitution method is at the heart of all encryption really, in one form or another, including in our present day. It’s just that our rules are more complicated.

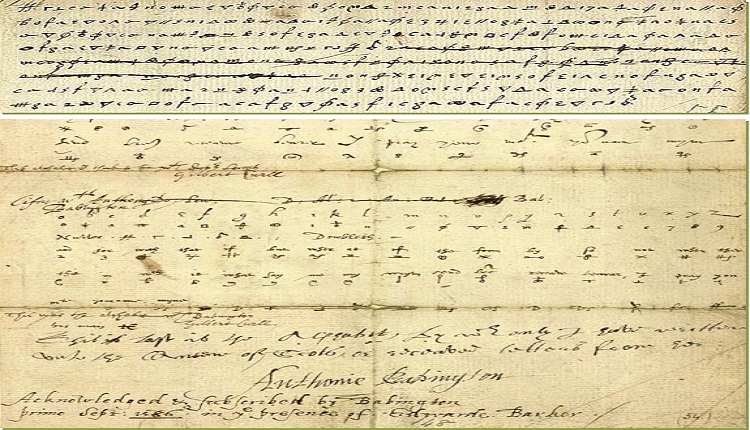

Mr. Babington, however, used a fixed form of substitution, the monoalphabetic cipher. This was well known in elite Catholic circles, with those using it committing the lines and shapes to memory. Anyone chancing upon a message written in this manner would be presented with a page filled with nonsensical slashing and dots and so on. Mr. Babington could be reasonably sure Mary would be able to unlock its contents.

The very existence of letters would bring immediate suspicion, of course. So the art of steganography was employed. Throughout the centuries, various methods were used to hide messages, including tattooing a poor serf’s freshly shaved head, waiting for follicles to conceal the missive, only then to have him sent off, head shaved again for reveal to the intended recipient. Ink that found its way through egg shells, with messages awaiting a good cracking, to contemporary versions of hiding messages within seemingly innocuous digital photographs are all examples of steganography.

Beer

Drinking water at the time was not as available as in our days, and so beer and spirits were common replacement. Mr. Babington was tipped off by a courier comrade that beer kegs, as a matter of weekly service, were delivered within Mary’s close proximity. Carefully folded notes could be smuggled, the courier insisted, without detection by way of slots in the barrels. Mary’s entourage, on business to fetch their lady drink, could then easily retrieve the note and hand it to her.

What the conspirators didn’t realize is Mr. Walsingham, protector of Elizabeth, had spies in every corner, lurking for just this purpose. That courier, so trusted by Mr. Babington, was at least a double agent, and dutifully brought the letter and plot to Mr. Walsingham. His instincts confirmed, Mr. Walsingham now had to set upon deciphering the note’s contents. History records few details about the code breaker tasked with the job, but his name was Thomas Phelippes.

Mr. Phelippes soon held a jumble of signs and slashes and dots. At the very least, each symbol represented a letter of the alphabet, one of twentysix. Multiplying each possibility yields the staggering number of 400 million billion billion. To get even a greater sense of what Mr. Phelippes was up against, had he worked around the clock at each possibility, it would’ve taken longer than what cosmologists have surmised as the age of the universe to make sense of Mr. Babington’s note to Mary.

Cryptanalysis had advanced from its early days, and shortcuts existed, leaving a principle to remain: letters when written down are not random, but instead follow well-worn patterns. Some letters are used more than others; still other letters hardly used at all. True too is how letters are often in companion, following one another regularly. Frequency analysis is the technique we recognize today used by Mr. Phelippes.

Gallows

The frequency of letters in English, for example, follow the pattern of where X and Y are used less than one percent, while the letter E turns up 12.7 percent. These are as true today as they were during Mr. Phelippes’ time. Letter proportions remain constant while they’re rearranged to our whim. But a savvy reader immediately sees how tasty an insight such as frequency analysis can be. It was only a matter of adding up the symbols and finding their relative percentages in order to break the code (short messages can foil frequency proportion predictions, however).

Finding, say, just two of the most commonly used letters within three spaces, T space E, could very well highlight the article THE. The document begins to give up its secrets with a few more inferences and time. And there it was: Mr. Phelippes’ translation indeed discovered Mr. Babington’s plot to gather support from foreign Catholics, assassinate Elizabeth, and rescue Mary. Mr. Babington went into excruciating detail, as he believed the note to be secure.

Mr. Babington’s fateful postscript

Mr. Babington’s fateful postscript

There was still one more step in Mr. Walsingham’s prosecution: confirming Mary approved. Mary Queen of Scots did exactly that in a letter back to Mr. Babington, incriminating herself deeply and without question. Once Mr. Phelippes finished with Mary’s letter of affirmation, he drew gallows upon it, noting it wouldn’t be long before she met her horrible fate.

Mr. Babington soon confessed under weight of Mr. Walsingham’s torture, and was given a public execution. Drawn by horse through the streets. Hanged, but cut down alive. Disemboweled. Mary too was arrested and put on trial. Mary claimed no connection to the plot. The letters, read aloud, condemned her. Reports detail a botched execution, taking three chops to finally remove her head. As a final indignity, the executioner set about raising the severed head of a traitor, only to have it slip from under a wig, as Mary’s hair had receded badly with age. Her severed head fell to the ground.

English cryptographic achievement into the 20th century often credit Mr. Phelippes’ efforts. Historians claim this was the final stand of any serious Catholic threat to protestant England. For our purposes, the affair can serve as a reminder of crypto’s many faceted components, its power, and relevance to our modern lives.

Do you have a favorite aspect of crypto history? Let us know in the comments!

Images via Pixabay, Wikipedia.

At news.Bitcoin.com we do not censor any comment content based on politics or personal opinions. So, please be patient. Your comment will be published.

The post Crypto History Part 1: 400 Million Billion Billion, Beer, and a Murderous Plot appeared first on Bitcoin News.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the views of Bitcoin Insider. Every investment and trading move involves risk - this is especially true for cryptocurrencies given their volatility. We strongly advise our readers to conduct their own research when making a decision.