Latest news about Bitcoin and all cryptocurrencies. Your daily crypto news habit.

What Could Blockchain Do for Music?

Imogen Heap. Photo: Man Alive on Flickr

Imogen Heap. Photo: Man Alive on Flickr

Musician Imogen Heap is addressing her audience from a stage in a giant tipi set up on the grounds of her home for an event to unveil the latest steps in her Mycelia project, which aims to use blockchain technology to solve some long-standing music industry problems.

“We could have a Napster times a thousand if we get it wrong with blockchain. If we don’t come up with solutions, somebody else will, and they won’t be on our terms.”

Imogen Heap announcing Mycelia

Imogen Heap announcing Mycelia

After Heap’s keynote, the attendees listen to talks and a panel session about blockchain. They also get a guided tour of her home studio and demos of technologies — including the Mi.Mu gloves that Heap developed — and then watch her play a concert in her nearby barn.

Why are 200 music and tech folk — from the CEO of the British Phonographic Industry (BPI) to the founders of startups like TheWaveVR, Jaak, and Blockpool — sitting in a big tent on the outskirts of London, on a day so cold that many are huddled under blankets supplied by Heap’s Mycelia colleagues?

Reimagine the Music Industry in a Data-Driven World

Respect, mainly. Heap has been an advocate for blockchain technology in the music world since 2015, when she released a song called “Tiny Human” with blockchain startup Ujo Music. Fans could choose to pay for the song using the Ether cryptocurrency; a smart contract automatically split the revenues between Heap and her collaborators.

Imogen Heap’s Mi.Mu music gloves. Photo: Harrison Weber on Flickr

Imogen Heap’s Mi.Mu music gloves. Photo: Harrison Weber on Flickr

The project received heavy media coverage, although also some criticism for the convoluted purchasing process, as well as questions about how commercially successful it was. Heap saw it more as an experiment—something she and others could learn from.

“It seemed sensible if we could reimagine the music industry and how it could work in a data-driven world. The music industry hasn’t really redefined itself or changed its business models in 100 years, yet here we had a completely new framework to work with,” Heap says now.

“Tiny Human” and Mycelia are neat illustrations of the two main areas of focus for applying blockchain technology to the music industry.

Cut Out the Middlemen

The first area is the radical disruption play: startups like Ujo that want to help artists sell their music directly to fans (ideally using cryptocurrency) with smart contracts that instantly split and pay the royalties, and with no need for traditional middlemen like labels, publishers, or collecting societies.

Gramatik at the Austin City Limits Festival, 2014. Photo: ACL on Flickr

Gramatik at the Austin City Limits Festival, 2014. Photo: ACL on Flickr

The extension of this is musicians minting their own cryptocurrencies. Dance artist Gramatik recently created the GRMTK token and raised just under $2.5 million by releasing 25 percent of them for fans and the crypto community to buy. Anyone holding GRMTK tokens will get a share of his royalties.

The second area is more of a partnership play: blockchain startups that want to help the music industry solve one of its long-standing problems—bad data. Or at least fragmented, siloed data; the lack of a single global database that brings together information from the recording and publishing sides of the music industry.

A big problem? Huge. Imagine a recording of a song that’s being streamed on a service like Spotify. Who wrote that song? Who are the publisher(s) collecting money for the songwriter? If it’s multiple songwriters, how are royalties split between them?

A Shared Global Database? Hmmm…

The last time the music industry tried to create a “global repertoire database” to make those questions easily answerable, the project collapsed in 2014 after £8 million in spending and lots of arguments between the project’s many cooks.

Three years on, this is where blockchain comes in — at least according to startups like Dot Blockchain, Jaak, and Blokur, which are focusing on this problem.

“We see the real use case of blockchain in the music industry as quite simple: We need one place to put all of the rights information…and a database is quite a bad place to put it,” Vaughn McKenzie, CEO of Jaak, said at the recent Slush Music conference’s blockchain panel.

“Lots of organizations that have lots and lots of data, they’re not really talking to one another, and their systems aren’t really talking to one another,” said Blokur’s Emma McIntyre at the same event. “The very nature of blockchain allows you to synchronize all of those databases, and that, for us, is where a lot of the value really comes from.”

(Every music industry conference includes a blockchain panel nowadays. “So many blockchain panels! There must be one a day,” says Heap at the Mycelia launch. One coffee break later, her stage plays host to that day’s example.)

McKenzie boiled the pitch down to a “big spreadsheet in the sky” of information on recordings and songs: Every entity involved is sharing their data, but it still belongs to them.

Creative Passports

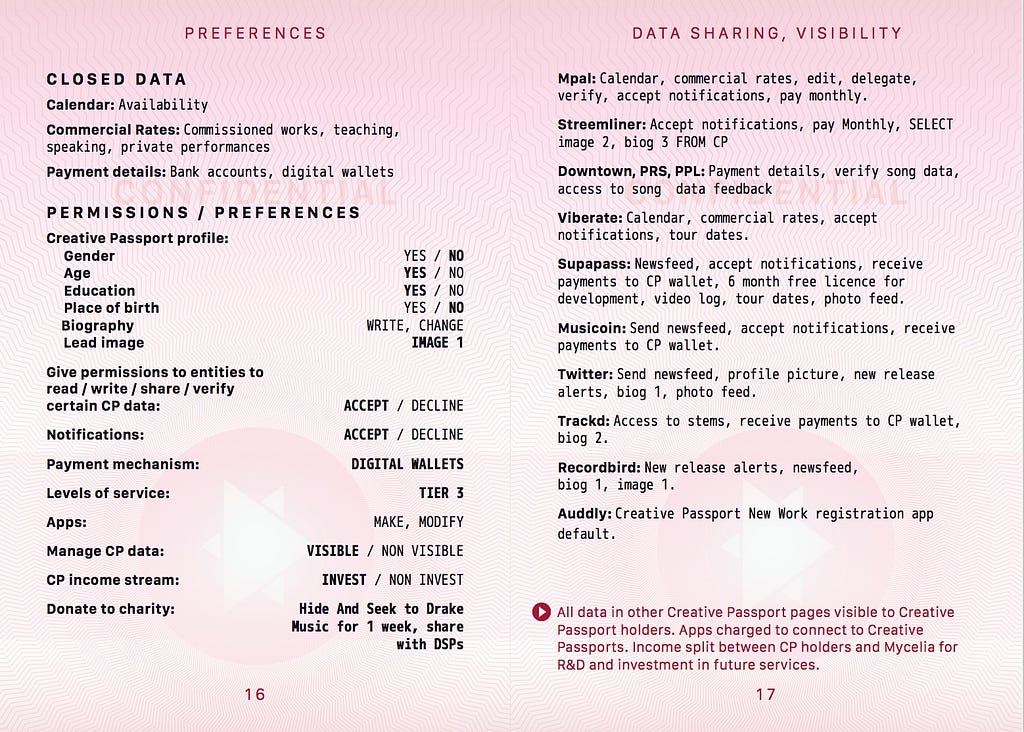

Mycelia has moved in to this world, too. At her event, Heap unveils something called a creative passport, which musicians will populate with all their data — from songwriting splits to remixing permissions — for blockchain-friendly digital music services to access.

“If you’re an artist, you want a hub, a connective hub between yourself and anyone who wants to do business with yourself or your songs,” Heap says. “Nobody should own the data but us, because we generate it.”

Heap and her team set off on a Mycelia-branded tour in 2018: a three-day music and tech festival visiting 40 to 45 cities over the course of the year. While signing up local musicians for creative passports is a key goal, Heap hopes it will also bring together artists, startups, music services, and individual developers for other kinds of creative collaboration.

There’s a lot of scepticism within the music industry about blockchain technology. Yes, some of that is people dismissing a technology they don’t understand, but plenty of it is people who do understand blockchain, and thus have well-developed bullshit filters for overconfident claims about destroying the middlemen or solving the great database problem.

We Need Prototypes in the Wild

There is a consensus, though, that what’s needed is more action rather than just words: actual blockchain music prototypes in the wild, and artists, managers, labels, publishers, and collecting societies getting hands-on experience of the potential strengths (and, yes, weaknesses) of the blockchain for music.

In that context, Mycelia’s creative passport, as well as Jaak’s plans for pilots with music rights-holders, Blockpool’s partnership with Björk to give fans cryptocurrency, Gramatik’s ICO, Dot Blockchain’s coalition of industry partnerships, and Ujo’s blockchain-powered online stores for musicians, all have a role to play.

Björk has already partnered with Blockpool.

Björk has already partnered with Blockpool.

“It’s a big vision. It might not all happen exactly as I’m presenting it. But if we don’t dream, nothing’s going to happen,” says Heap as she closes her keynote.

“What is the architecture of the world that we want it to be?” adds musician (and early blockchain advocate) Zoe Keating in the follow-up panel. She suggests that the blockchain — unlike some previous technology shifts for the music industry — could be artist-centred from the start.

“It’s a chance not to have that architecture built by companies who want to optimize it for their bottom line.”

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the views of Bitcoin Insider. Every investment and trading move involves risk - this is especially true for cryptocurrencies given their volatility. We strongly advise our readers to conduct their own research when making a decision.