Latest news about Bitcoin and all cryptocurrencies. Your daily crypto news habit.

Back in the early 1990s, when I was still in grad school and just beginning to think about a career writing outside of academia, I wrote a little essay that I think was called “The Politics of Software.” Loosely inspired by an Umberto Eco riff about the quasi-religious differences between followers of Macintosh and DOS-based platforms, the essay tried to make the argument that we were headed towards a world where championing different software architectures would have political implications. You wouldn’t just choose one operating system over another one just because one was more user-friendly, or less inclined to crash. (This was pre-Web, so piece wasn’t about the Internet at all, as I recall.) You’d also choose one OS over the other because its design resonated with your larger worldview about how society should be organized, or how wealth should be shared, or how much control large corporations should have in the world.

I shopped the piece around to junior editors I knew at The New Republic and The Village Voice, but no one picked it up. (It took another year or two before I published my first piece, in The Guardian.) I’d love to believe they passed on it because it was too visionary and ahead of the curve, but I think the more likely explanation is that it just wasn’t very convincing, in part because the social impact of the technology wasn’t at all clear (to me as much as anybody) at a time when people were mostly using computers for the word processors and spreadsheets.

But over the years, the link between politics and software platforms continued to be a recurring theme in my work: it shows up in my first two books, Interface Culture and Emergence, and then in my 2012 book, Future Perfect. This week, as it happens, I have two long essays running in The New York Times Magazine and in Wired that meditate on the political implications of software platforms in a networked age.

The Times Mag piece began almost a year ago, as an attempt to take stock of the wreckage of 2016. There was a growing chorus of complaints — most of which I agreed with — that the Internet was broken, but very little talk about how we might go about fixing it. So with the encouragement of my brilliant editor at the Times, Bill Wasik, I set out to try to assess what are options were in terms of making structural changes that would address the problems that had become so apparent. That ultimately led me to the blockchain. The more I dug into the potential of these new technologies, the more promise I started to see. And yet at the same time, as the piece started to take shape, the blockchain world was increasingly overrun by Bitcoin/ICO mania, with a parade of scam artists and charlatans dominating the space. So the piece tries to wrestle with both those ideas: the blockchain is both a giant bubble, and maybe our only hope:

Much has been made of the anarcho-libertarian streak in Bitcoin and other nonfiat currencies; the community is rife with words and phrases (“self-sovereign”) that sound as if they could be slogans for some militia compound in Montana. And yet in its potential to break up large concentrations of power and explore less-proprietary models of ownership, the blockchain idea offers a tantalizing possibility for those who would like to distribute wealth more equitably and break up the cartels of the digital age… Yes, the blockchain may seem like the very worst of speculative capitalism right now, and yes, it is demonically challenging to understand. But the beautiful thing about open protocols is that they can be steered in surprising new directions by the people who discover and champion them in their infancy. Right now, the only real hope for a revival of the open-protocol ethos lies in the blockchain… If you think the internet is not working in its current incarnation, you can’t change the system through think-pieces and F.C.C. regulations alone. You need new code.

Even though the Times was generous enough to give me 9,000 words (!!) to explore the blockchain, there were still a number of ideas and sources that I wasn’t able to reference in the piece. One of the essays that really opened my mind in researching these ideas is a blog post called “Fat Protocols,” written by the crypto VC Joel Monegro. And while Chris Dixon is quoted several times in the piece, his Medium essay from last summer “Crypto Tokens: A Breakthrough In Open Network Design” is well worth a read.

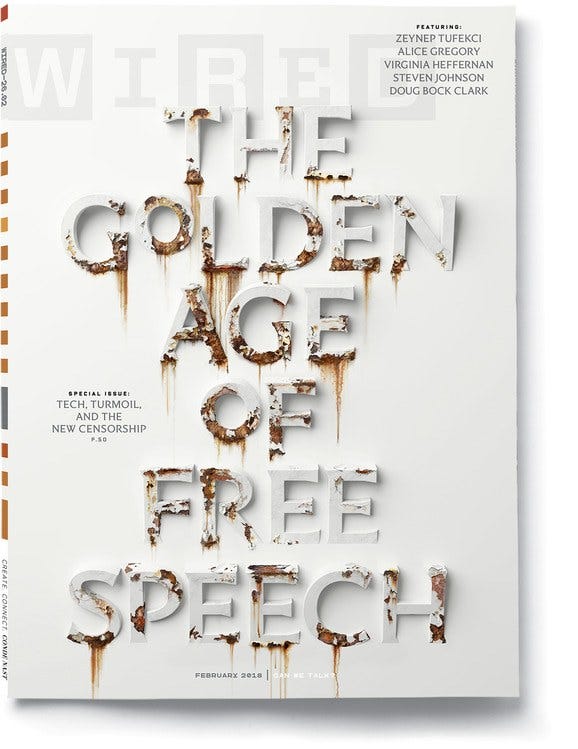

My Wired piece is part of a powerful new special issue they’ve just published devoted entirely to the question of free speech online. You’ll want to start with Zeynep Tufecki’s opening essay, “It’s The (Democracy-Poisoning) Golden Age of Free Speech.” Zeynep is one of my very favorite thinkers on politics and protest in an age where information is increasingly shaped by invisible algorithms, and this piece makes a persuasive argument that the way we’ve been trained to think about free speech issues no longer applies when attention, not a publishing platform, is the scarce resource.

My contribution to the issue is a story about the Internet infrastructure company Cloudflare and their public tangle last summer with the Neo-Nazi site The Daily Stormer. The piece tries to wrestle with the obligations of private Internet companies — and particularly low-level platforms like Cloudflare that operate below the awareness of ordinary consumers — to police offensive speech. It’s a new genre for me, as a work of journalism, in that the main torso of the story is a “tick-tock” that tells the hour-by-hour tale of how Cloudflare dealt with the crisis, ultimately deciding to expel Daily Stormer, but at the same time publishing a blog post explaining why that was a terrible idea. It ends with a long section probing some issues close to the ones that Zeynep explored in her piece:

The immense size of the gatekeepers — like Google, Facebook, Twitter and, in its own way, Cloudflare — has also challenged the older vision of cyberspace as a realm of unchecked speech. There have been dark wells of hate online since the Usenet era, but back then, misanthropy was distributed across thousands of different platforms. Even if you felt some speech was objectionable enough to silence, it was a practical impossibility to get rid of it all. No single entity could silence an idea. But in a world where Facebook and Google count their audiences in the billions, a decision by one of those big players could, essentially, quiet an unpopular voice.

The other news this week is that I’m finally jumping on the bandwagon with just about every other nonfiction writer I know and starting an email newsletter. (The text of this Medium post is, more or less, the content of the first mailing.) I’m excited about this project, not the least because of its back-to-the-future feel. These emails will be a monthly affair except when I have a new book or some other project out, at which point it may become bi-weekly for a stretch. My goal is to have the newsletter take on the tone and structure of the emails I used to send to friends back in the early days, right around when I was writing that failed essay on the politics of software: emails that took their cue from longer-form correspondence from the snail mail age, where you’d tell a story or make an argument, or give a richer status update on what’s going on in your life. The topics will include my usual suspects: long-term thinking, play, tools for the creative mind, long zoom histories, peer politics, new healthcare advances, and whatever else I happen to be writing and thinking about. If that sounds like fun, you can sign up in the form below.

The Politics Of Software was originally published in stevenberlinjohnson on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the views of Bitcoin Insider. Every investment and trading move involves risk - this is especially true for cryptocurrencies given their volatility. We strongly advise our readers to conduct their own research when making a decision.